E. Donnall Thomas, Joseph Murray-Most Influential Doctors

Old man death has not had such an easy time since these next two “most influential doctors of all time” came on the scene.

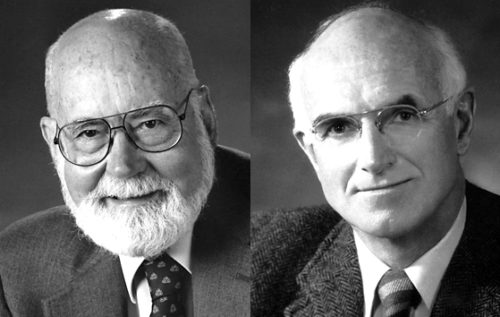

Dr. E. Donnall Thomas and Dr. Joseph E Murry, both received the 1990 Nobel prize for their independent lifetime of work against cancer and the life-saving techniques they developed and pioneered.

1990 Nobel Prize awarded jointly to Drs E. Donnall Thomas and Joseph Murray for “discoveries concerning organ and cell transplantation in the treatment of human disease”

We’re at number 31 in our list of the 50 all-time most influential doctors proposed by a leading medical magazine, and it’s difficult to choose how to list these physicians separately.

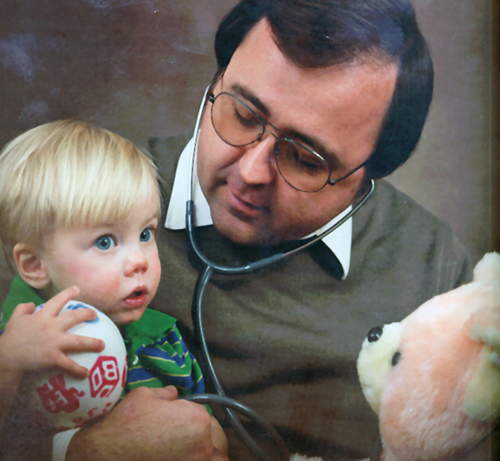

So, just like the Nobel Prize committee, we’ll have to list them together: Dr. Edward Donnall “Don” Thomas developed bone marrow transplantation as a successful method to treat leukemia and Dr. Joseph Edward Murray did similarly for kidney failure by transplanting kidneys.

Edward D Thomas (1920-2012) and Joseph E Murray (1919-2012) – #31

Defeaters of Cancer, Winners of Nobel Prize

Working separately in their life’s-work against leukemia and kidney failure but together in the field of cancer, neither were deliberately seeking notoriety or even considering that merely putting their best work into caring for their patients would lead to a Nobel Prize. After all, those went to “test tube people” not to workers in the trenches.

But by 1990, both of them had been noticed by their peers so intently that “bean counters,” politicians—and even Nobel Prize committees—were compelled to take note and act.

Edward D Thomas (1920-2012)

Edward D Thomas was born on March 15, 1920 in Mart, Texas, a rural town about 100 miles south of Dallas, putting him square on a trajectory toward doing his schooling and beginning his life’s work during the “great depression” in the U.S.

Early Life and Education of Edward D Thomas

His father, Dr. Edward E. Thomas, had come to Texas in a covered wagon and grown up on the frontier without much formal schooling; but was able to enter the University of Louisville, Kentucky, where he received his M.D. degree. His first wife had died of Tuberculosis and “Edward D” was the only child of his second wife Angie Hill Donnall, a teacher.

When Don was born his father was 50 and a solo general practitioner so it was natural that the two had plenty of opportunities to be together on “house calls” around the small village. He learned to hunt and fish, and as an adult, he would unwind after a hard day by filling shells with gunpowder.

Don’s high school class consisted of about 15 people and he didn’t really catch on to schooling until the curriculum became more difficult and appealing. He entered the University of Texas at Austin studying chemistry and chemical engineering and earned both a BA and MA in the field.

Money was non-existent during that time so he earned his way with odd jobs. After a shift waiting tables he recounted being hit in the face with a snowball thrown by a Dorothy E. “Dottie” who later changed her last name to Thomas and became constantly by his side, even in his research.

Don entered Harvard Medical School under a U.S. Army program and Dottie gave up her journalism career to first support them and then become his research assistant (and thus the “mother of bone-marrow transplants,” but we get ahead of ourselves).

In the years following graduation, an internship, a year of hematology training, two years in the army, a year of postdoctoral work at MIT and two years of medical residency he developed an interest and passion for the bone marrow and leukemia. He saw the first child go into remission with an anti-folate drug as well as met Dr. Joseph Murray and helped care for his first kidney transplant patient.

Later life:

While some breakthrough therapies are results of happy accidents, Dr. Thomas’s work resulted from nothing “accidental.” Systematic research producing reasoned insights leading to laboratory trial and error, multiple setbacks and hard-earned successes was what eventually earned him the title of “the Father of Bone Marrow Transplants.”

His belief that marrow transplantation would cure leukemia was a bit novel but supported by many observations and data from reports of people and animals subjected to lethal radiation but who had recovered when cells in their spleen or bone marrow had been protected from the radiation and had a chance to re-grow back into the body.

He had to develop a method of tissue-typing dogs in the process and had many of his first patients go on to die until the many and varied problems could be solved.

His own autobiographical writings state that it was difficult to tease out the threads of his life that lead to the various developments and gave credit to the constant association with many good researchers over a prolonged time at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the other places he had worked.

Eventually his techniques would lead to cures in some patients with advanced leukemia, aplastic anemia and genetic diseases. All of that led to his 1990 Nobel Prize, shared with his long time friend and colleague Joseph Murray, and the National Medal of Science.

He died at 92 of heart failure in in Seattle Washington on October 20, 2012; but not before being able to attend a 30-year reunion of over 300 patients he and his wife had helped cure using his pioneering techniques.

Biographic Summary

Edward D Thomas was an American physician and researcher

Born: March 15, 1920, Mart, Texas, US

Died: October 20, 2012 (92), Seattle, Washington, US

Education: U of Texas at Austin, Harvard Medical School

Known for: Developing and performing Bone Marrow Transplant techniques; curing leukemia and other blood disorders

Awards: Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, National Medal of Science in 1990

Parents: Dr. Edward E. Thomas, rural physician; Angie Hill Donnall, teacher

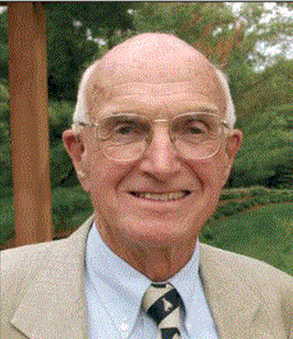

Joseph E Murray (1919-2012)

Early Life and Education of Joseph E Murray

Joseph E Murry was born April 1, 1919 in Milford Massachusetts to William A. and Mary (née DePasquale) Murray of Irish and Italian descent. He excelled in football and became a star athlete at the Milford High School in addition to ice hockey, and baseball.

He attended the College of the Holy Cross intending to play baseball but conflicts between baseball practices and lab schedules forced him to give up baseball. With a degree in humanities in 1940 Murray entered Harvard Medical School then interned at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and inducted into the Medical Corps of the U.S. Army.

He served in the plastic surgery unit at Valley Forge General Hospital in Pennsylvania caring for thousands of soldiers wounded on the battlefields of World War II reconstructing their disfigured hands and faces especially those who were burned. That was when he noticed that burn victims rejected temporary skin grafts from unrelated donors much more slowly than had been expected, suggesting the potential for organ grafts, or transplants.

Later life:

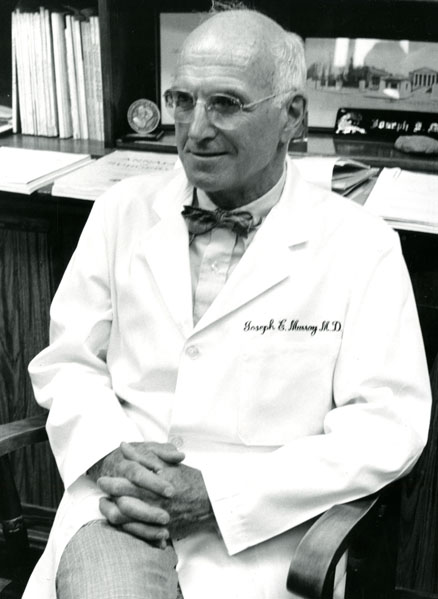

Eventually he led a team of Harvard physicians to solve the dilemma of organ rejection and On December 23, 1954 performed the world’s first successful renal transplant between the identical Herrick twins in an operation that lasted five and a half hours. A healthy kidney donated by Ronald Herrick was transplanted into his twin brother Richard, who was dying of chronic nephritis granting him eight more years of life.

In 1959, Murray went on to perform the world’s first successful allograft and, in 1962, the world’s first cadaveric renal transplant becoming an international leader in the study of transplantation biology, the use of immunosuppressive agents, and studies on the mechanisms of rejection.

Eventually his work led to the new drug Imuran and other anti-rejection drugs for use in transplants which allowed transplants from unrelated donors. By 1965, the survival rates from unrelated donors exceeded 65%.

Murray trained physicians from around the world in transplantation and reconstructive surgery, frequently performing surgeries in developing countries; retiring as professor of Surgery Emeritus in 1986 from Harvard Medical School.

In 1990, he was honored with the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his pioneering work in organ transplantation along with his friend E. Donnall Thomas.

He suffered a stroke at his suburban Boston home on Thanksgiving and died at Brigham and Women’s Hospital on November 26, 2012, aged 93.

Murray is featured in the book Beyond Recognition, previously titled Camel Red. The book is the story of Larry Heron, who was very seriously injured in World War II, and his road to recovery, which reunited him with Murray, a former classmate.

Biographic Summary

Joseph Edward Murray was an American plastic surgeon Nobel Prize winner for kidney transplants

Born: April 1, 1919, Milford Massachusetts

Died: November 26, 2012 (93), Boston, Massachusetts

Education: College of the Holy Cross and Harvard Medical School

Known for: First successful Kidney transplant

Books: Surgery Of The Soul: Reflections on a Curious Career (autobiography)

Parents: William A. and Mary (née DePasquale) Murray

Awards: Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1990

25 Posts in Top 50 Doctors (top50) Series

- 27 - Charles D. Kelman - Cataracts – 9 Mar 2023

- 28 - Cicely D. Williams, Kwashiorkor, Breastfeeding, Whistleblower – 21 Jun 2022

- 29 - Dame Cicely Saunders, Hospice – 23 Apr 2018

- 30 - David L. Sackett, Evidence-based Medicine – 2 Apr 2018

- 31 - E. Donnall Thomas & Joseph Murray, Bone Marrow Transplants – 23 Feb 2018

- 32 - Elizabeth Blackwell, women in medicine – 29 Jan 2018

- 33 - Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, stages of grief – 5 Jan 2018

- 34 - Watson & Crick, DNA – 2 Dec 2017

- 35 - Mahmut Gazi Yaşargil, Micro-Surgery – 24 Oct 2017

- 36 - George Papanicolaou, Cytopathology, Cancer – 29 Sep 2017

- 37 - Dr. James Parkinson, Parkinson's Disease – 1 Sep 2017

- 38 - Dr. John Snow, cholera – 20 Aug 2017

- 39 - Dr. Joseph Kirsner, GI Joe – 27 Jul 2017

- 40 - Lawrence (Larry) Einhorn, chemotherapy – 16 Jun 2017

- 41 - Robert Koch, modern bacteriology – 21 Mar 2017

- 42 - Stanley Dudrick, TPN – 28 Feb 2017

- 43 - Stanley Prusiner, neurodegenerative diseases – 25 Jan 2017

- 44 - Victor McKusick, medical genetics – 3 Jan 2017

- 45 - Virginia Apgar, anesthesiology & newborn care – 12 Nov 2016

- 46 - William Harvey, circulation – 12 Oct 2016

- 47 - Zora Janžekovič, burns – 26 Sep 2016

- 48 - Helen Taussig, blue babies – 3 Sep 2016

- 49 - Henry Gray, anatomy – 3 Jul 2016

- 50 - Nikolay Pirogov, field surgery – 11 Jun 2016

- Top 50 Doctors: Intro/Index – 10 Jun 2016

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)