Most Influential Doctor: David L. Sackett – Evidence-based Medicine

Medicine has a lot of “fathers” of various things; and many of the “50 most influential physicians of all time” we’ve been talking about have been considered “fathers” of one thing or another.

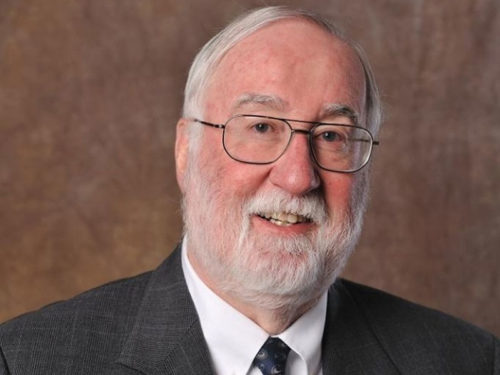

Dr. David L. Sackett is no exception—A “father” of evidenced based medicine, number 30 on our list.

David L. Sackett, “father” of evidenced-based medicine

The problem is that, as ubiquitous as it has become in medicine, the term “Evidenced Based Medicine” (EBM) in a discussion sort of falls flat to the floor with a thud!

Unlike other monikers that “ring” like: “transparency in government”, “progressive enhancement” or even “alternative medicine”, using the term EBM garners blank looks—even though the term is much more understandable than any of the other three I mentioned.

After all, haven’t we ALWAYS used evidence in deciding how we practiced medicine? I mean, if we’re just starting now, what did we use back “then”?

David L. Sackett (1934-2015) – #30

The “Father” of Evidence-Based Medicine

Yes, there is no other way to practice legitimate medicine than to use “evidence” and “real doctors” have always done it; BUT, there is “evidence” and there is “evidence”—and Sackett figuratively and literally “flipped on the light.”

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) uses the “best evidence” from well-designed and conducted research to optimize the whole decision-making process; and goes a step further by classifying each piece of evidence by its “strength” of being true knowledge.

EBM counts data from meta-analyses, systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials as “strong” evidence, that from case-control studies as “weaker” and that from personal observation and opinion as the “weakest” of all. Then, the decisions/recommendations based on each of these three types are considered “strong,” “weaker” and “weakest” too.

Initially EBM described decisions by individual physicians for individual patients; but these days it has expanded into every nook and cranny of medicine: guidelines and policies about patients and populations.

Early Life and Education of David Lawrence Sackett

David Lawrence Sackett was born November 17, 1934 in Chicago, Illinois to an artist, DeForest Sackett and his wife Margaret (Ross). I literally cannot find any biography for him until reference that he earned his medical degree from the University of Illinois and trained as an internist and nephrologist.

He had just set up his laboratory after graduation when the 1962 Cuban missile crisis got him drafted and assigned to the US Public Health Service and billeted to the Chronic Disease Research Institute in Buffalo, New York. He was a chief teaching fellow and began studying for an Masters of Science (MSc) at Harvard.

When he earned the degree in epidemiology from Harvard he was recruited, in 1967, to the brand new McMaster University medical school in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada where he immediately set to re-defining approaches to teaching medicine—and writing the now-standard textbook of clinical epidemiology.

He was only 32 and now the founding chair of clinical epidemiology and biostatistics—beginning his First Career and coining the term “clinical epidemiology.”

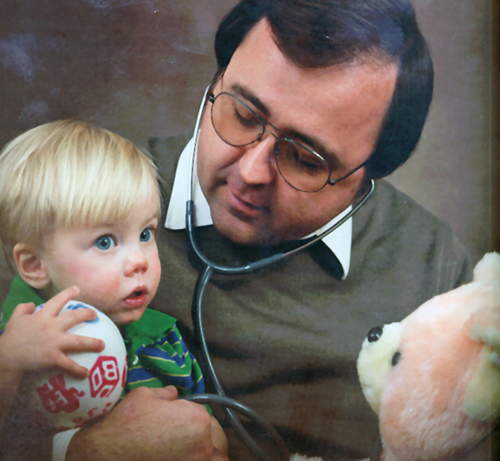

Everyone who knew him first had heard about his “rolling evidence cart,” a novel cart with a computer, compact discs of MEDLINE and other databases, texts, guidelines… and a projector that could be rolled with him down the halls with medical students as he taught them medicine from one patient’s room to the next. Now days, all physicians can do the same thing with their “smartphones.”

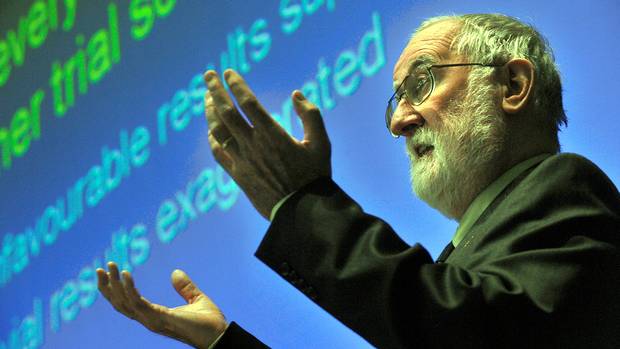

By the late 1970s, the “Sackett process” began to become popular within medical education. No matter the topic, his approach was similar. He would say, for example: “suppose you detect 10 to 15 degrees of scoliosis in an otherwise healthy 12-year-old student who has come for her preschool examination. Do you tell her and her parents (and, if so, what do you say?), refer her to an ‘orthopod’ or what?”

Every topic had a “hook” like this for his process: (1) structure a researchable question, (2) select the most likely resource, (3) design an effective search strategy, (4) summarize and critique the evidence, (5) apply the evidence to the patient of interest, and (6) evaluate the process and outcome.

In the late ’80s his second career began developing and promoting extensive collaboration in clinical trials, which was no small amount of effort and took a real statesman to align all the different agendas of the participants.

His “third career” was dedicated to developing and disseminating various “critical appraisal” strategies for clinicians practicing medicine; and you may remember when all the doctors began promoting the daily use of baby-aspirin to prevent heart attacks.

That was Sackett and 12 other colleagues who published their 1985 report that daily aspirin decreased cardiac death and heart attacks. By then he had determined that he was already getting out-of-date and due for a “re-treading” so he had quit his post and was repeating his internal medicine residency—2 decades after his first round of training… his “fourth career.”

He became Physician-in-Chief at Chedoke-McMaster Hospitals, his “fifth career”; then, Head of the Division of General Internal Medicine for the Hamilton region, his “sixth career”.

By the ’90s he had helped develop the techniques of “meta-analysis” to analyze different studies on the same subject into a larger, more universal comparison than they were originally designed for.

He began his “seventh career” in 1994 when he moved to Oxford and became Foundation Director of the National Health Service at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Foundation Chair of the Cochrane Collaboration Steering Group, and Foundation Co-Editor of Evidence-Based Medicine.

Later life:

In 1999 he formally retired and returned to Canada where he began his “eighth career”: the Trout Research & Education Centre. He participated in over 200 randomized clinical trials over his career in addition to publishing 12 books, chapters for about 60 others and over 300 papers in medical and scientific journals.

In retirement, he and his wife Barbara (Bennett), whom he had married after his first year of medical school, turned their home near Lake Huron, Ontario, into a center for teaching workshops.

He died of cholangiocarcinoma May 13, 2015 in Markdale, Ontario, Canada and was survived by his wife Barbara, their four sons (David, Charles, Andrew and Robert), his brother Jim, eight grandsons, hundreds of students and thousands of friends including those who initially opposed his efforts and were proven wrong.

Biographic Summary

David L. Sackett was an internist, epidemiologist, teacher and researcher

Born: November 17, 1934, Chicago, IL

Died: May 13, 2015, Markdale, Ontario, Canada

Education: University of Chicago School of Medicine, Harvard University

Known for: “Father” of evidence-based medicine

Books: Multiple

Parents: DeForest and Margaret (Ross) Sackett

25 Posts in Top 50 Doctors (top50) Series

- 27 - Charles D. Kelman - Cataracts – 9 Mar 2023

- 28 - Cicely D. Williams, Kwashiorkor, Breastfeeding, Whistleblower – 21 Jun 2022

- 29 - Dame Cicely Saunders, Hospice – 23 Apr 2018

- 30 - David L. Sackett, Evidence-based Medicine – 2 Apr 2018

- 31 - E. Donnall Thomas & Joseph Murray, Bone Marrow Transplants – 23 Feb 2018

- 32 - Elizabeth Blackwell, women in medicine – 29 Jan 2018

- 33 - Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, stages of grief – 5 Jan 2018

- 34 - Watson & Crick, DNA – 2 Dec 2017

- 35 - Mahmut Gazi Yaşargil, Micro-Surgery – 24 Oct 2017

- 36 - George Papanicolaou, Cytopathology, Cancer – 29 Sep 2017

- 37 - Dr. James Parkinson, Parkinson's Disease – 1 Sep 2017

- 38 - Dr. John Snow, cholera – 20 Aug 2017

- 39 - Dr. Joseph Kirsner, GI Joe – 27 Jul 2017

- 40 - Lawrence (Larry) Einhorn, chemotherapy – 16 Jun 2017

- 41 - Robert Koch, modern bacteriology – 21 Mar 2017

- 42 - Stanley Dudrick, TPN – 28 Feb 2017

- 43 - Stanley Prusiner, neurodegenerative diseases – 25 Jan 2017

- 44 - Victor McKusick, medical genetics – 3 Jan 2017

- 45 - Virginia Apgar, anesthesiology & newborn care – 12 Nov 2016

- 46 - William Harvey, circulation – 12 Oct 2016

- 47 - Zora Janžekovič, burns – 26 Sep 2016

- 48 - Helen Taussig, blue babies – 3 Sep 2016

- 49 - Henry Gray, anatomy – 3 Jul 2016

- 50 - Nikolay Pirogov, field surgery – 11 Jun 2016

- Top 50 Doctors: Intro/Index – 10 Jun 2016