10 Travel Diseases to Consider Before and After the Trip

The summer travel season is upon us, at least here in the U.S., and for most of us it means dusting off the car games for the kids to use between bathroom stops as we cruise across the country on vacation.

US family on vacation

For a few ‘lucky’ ones who can afford the ever increasing fees and regulations it might mean an airplane ride. For a few less, a jaunt across a border requiring a passport.

There are a few things we ought to keep in mind – medically speaking – in order to avoid experiencing a vacation that just “keeps on giving” long after you’d like it to be over.

Of course our level of concern should be greater related to the number of “borders” we cross going around the loop to back home. States, countries, continents get increasingly more “risky” – medically speaking.

Travel Diseases To Consider

We’ll not talk about hygiene here. You should already realize that you can’t get away with being as lax with your personal hygiene when you travel as you get away with at home. Not washing after doing your toilet, before eating or touching your face and mouth is a boatload more risky anywhere else but home, where you already have contracted your “home” bugs and gotten over them.

A “spit and a wipe” doesn’t cut it when you’ve just touched a knob containing influenza virus. And lazily leaving the door/window open has more consequences when THESE mosquitos have Malaria or Chikungunya virus.

So, let’s get the “elephant in the room” out of the way first. Even though it’s by far the smallest of our risks its outcome is so draconian (death) that we surely must give it at least a passing consideration: Ebola

Ebola

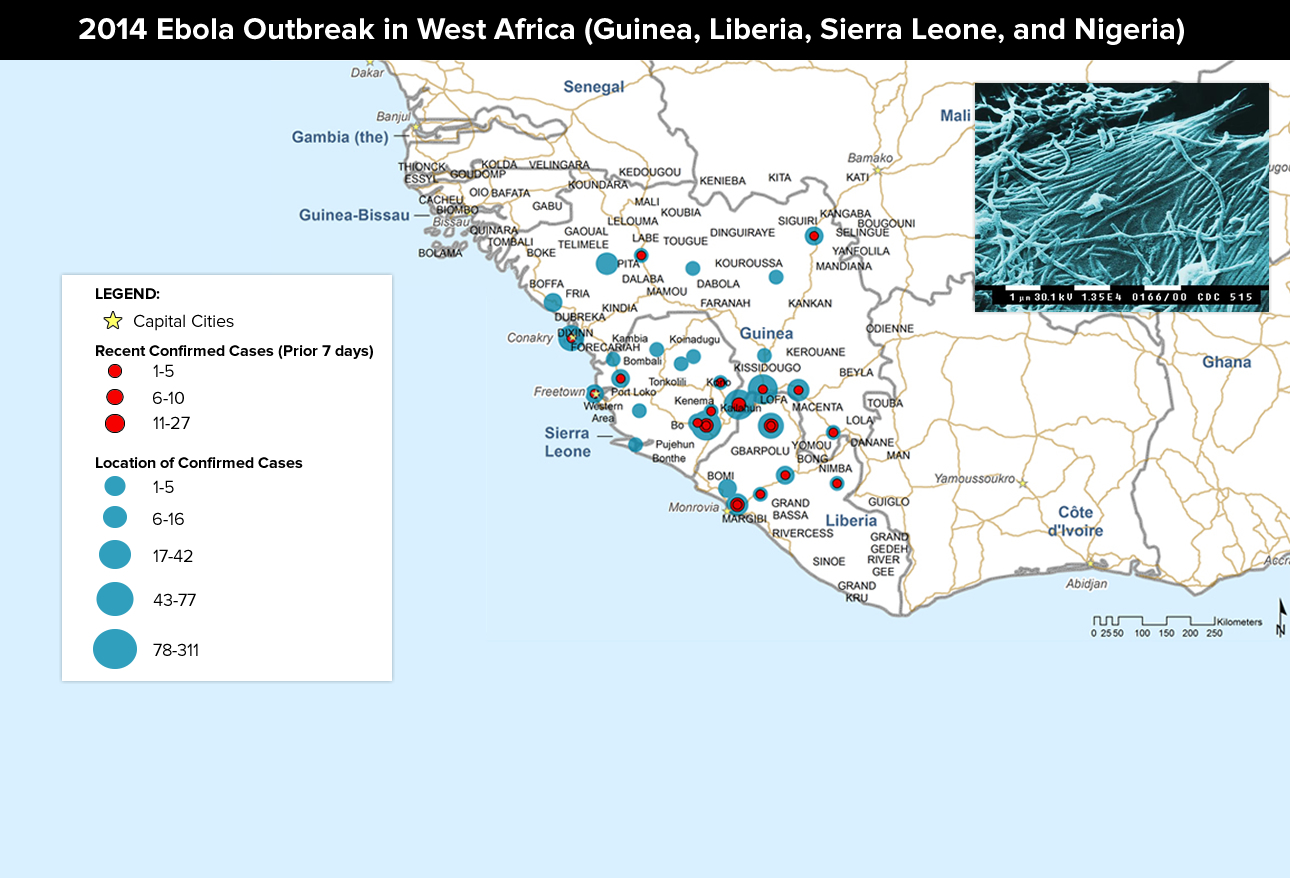

Ebola disease (formerly Ebola hemorrhagic fever) is caused by a virus and has, so far, eluded all public health efforts toward prevention or eradication. Wild animals transmit the virus to humans where it then can spread to others by direct contact or exposure to blood, organs, or secretions; or to objects that have been contaminated with such secretions (eg, needles).

Recent outbreaks have mainly occurred in remote villages of Central and West Africa (shown) near tropical rain forests. Ebola is an extremely severe and often fatal condition which is frustratingly difficult to diagnose until it’s in its late stages; because, early symptoms mimic so many other diseases. Within 2 weeks of exposure symptoms include arthritis, low back pain, fever/chills, fatigue/malaise, headache, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and sore throat – all of which could also be such diseases as malaria, typhoid fever, shigellosis, cholera, leptospirosis, plague, rickettsiosis, relapsing fever, meningitis, hepatitis, and other viral hemorrhagic fevers. See what I mean?

Then late symptoms begin: bleeding from the eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and rectum; conjunctivitis; genital swelling; increased pain in the skin; and hemorrhagic rash over the entire body. Uncontrolled bleeding (DIC), shock, and/or coma may occur. There are some expensive and difficult laboratory tests which can be done but diagnosis is first by excluding other things AND an index of suspicion due to possible exposure.

Once diagnosed, treatment is under extreme hazmat conditions but may be too late to prevent spread. There is no licensed vaccine and no known cure; existing antivirals are ineffective against Ebola. Infected patients are usually hospitalized, and most require intensive supportive care to manage shock and/or infections. Up to 90% of patients die of the disease and it is one of the most dangerous diseases for health care workers.

WHAT TO DO: “Eluding all public efforts toward prevention” means that the only protection is not even to go anywhere close to the disease; but, even that doesn’t stop some infected person from running into you. Meticulous hygiene and avoidance of potential carriers and vectors are about all you can do.

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)

The virus (Coronavirus MERS-CoV) that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) originally came from Camels but it’s now pretty much human-human spread through airborne respiratory secretions and close personal contact. Original cases crop up in the middle-east but all other countries, including the U.S., need to treat secondary infections from travelers.

No vaccine or specific treatment is available so supportive therapy to maintain vital organ functions is all we can do.

WHAT TO DO: Preventive measures include frequent hand-washing (like your mother says you should not your dad) for at least 20 seconds – with soap! As well as not touching your face with unwashed hands, covering your nose/mouth with a disposable tissue to cough/sneeze, avoiding close personal contact, not sharing tableware/utensils with ill persons, and frequent cleaning/disinfecting of often-touched surfaces.

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV)

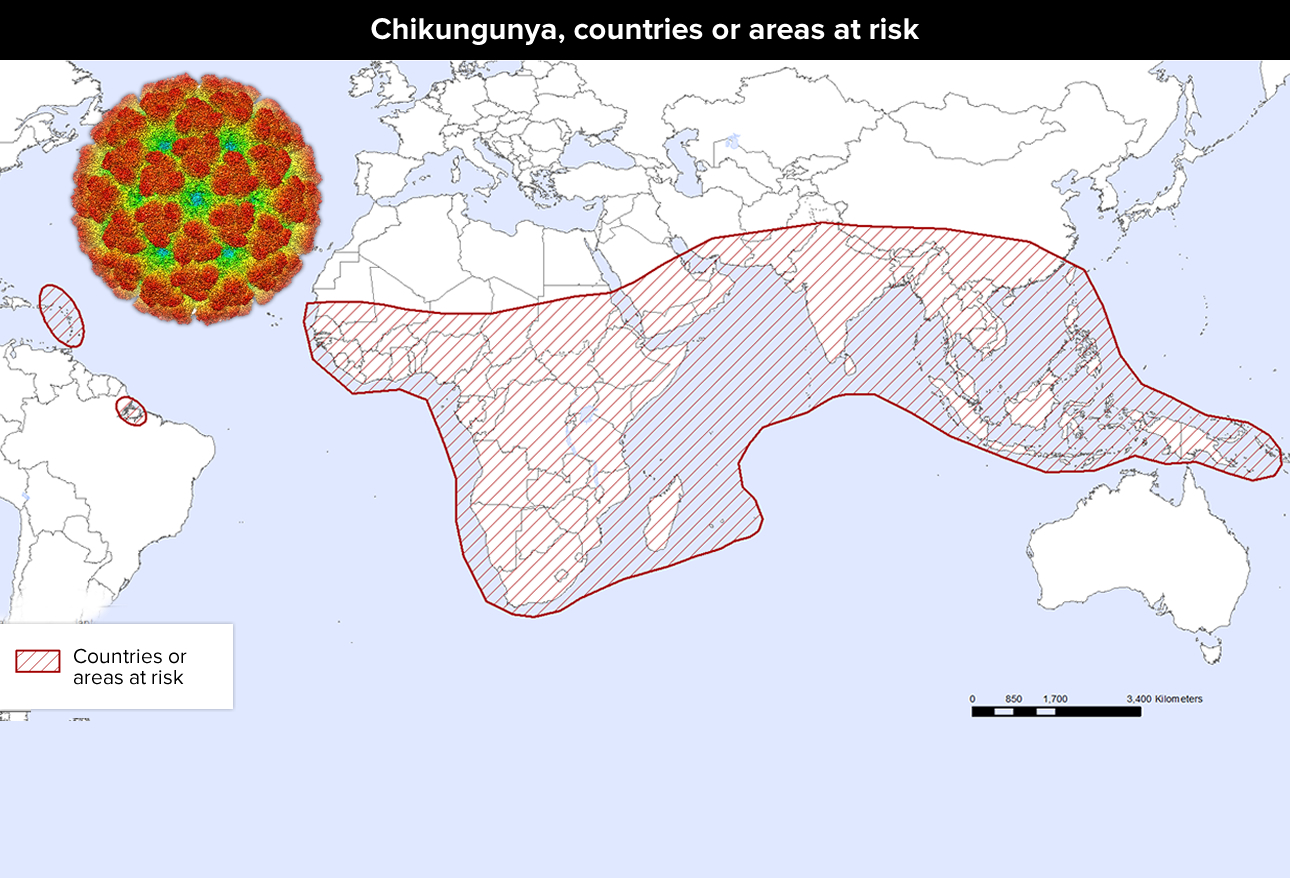

The female Aedes mosquito which carries and spreads the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) began in Africa, Asia, Europe and Pacific but are now inhabiting the Caribbean and Americas. The muscle and joint pain, headache and rash which it produces can be confused with dengue fever so diagnosis is difficult; but, the treatment is the same for both: just treat the symptoms. Joint pain can persist for months.

Particularly at risk for more severe disease include perinatally infected newborns, adults over 64 and people weakened by other diseases. It’s the day-and-night activity of the mosquitoes and their breeding proximity to humans which controls the risk for contracting CHIKV infection.

WHAT TO DO: A lot easier said than done, one must eliminate/reduce the number of artificial water-filled containers and natural habitats that act as mosquito breeding grounds and avoid Aedes mosquito bites! Do that by: wearing permethrin-treated clothing that minimizes skin exposure; using insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, oil of lemon eucalyptus/PMD, or ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate [IR3535]; and, using window/door screens and bed nets. There is no vaccine or specific drug to treat CHIKV infection; prevention is the best countermeasure.

Measles (rubeola)

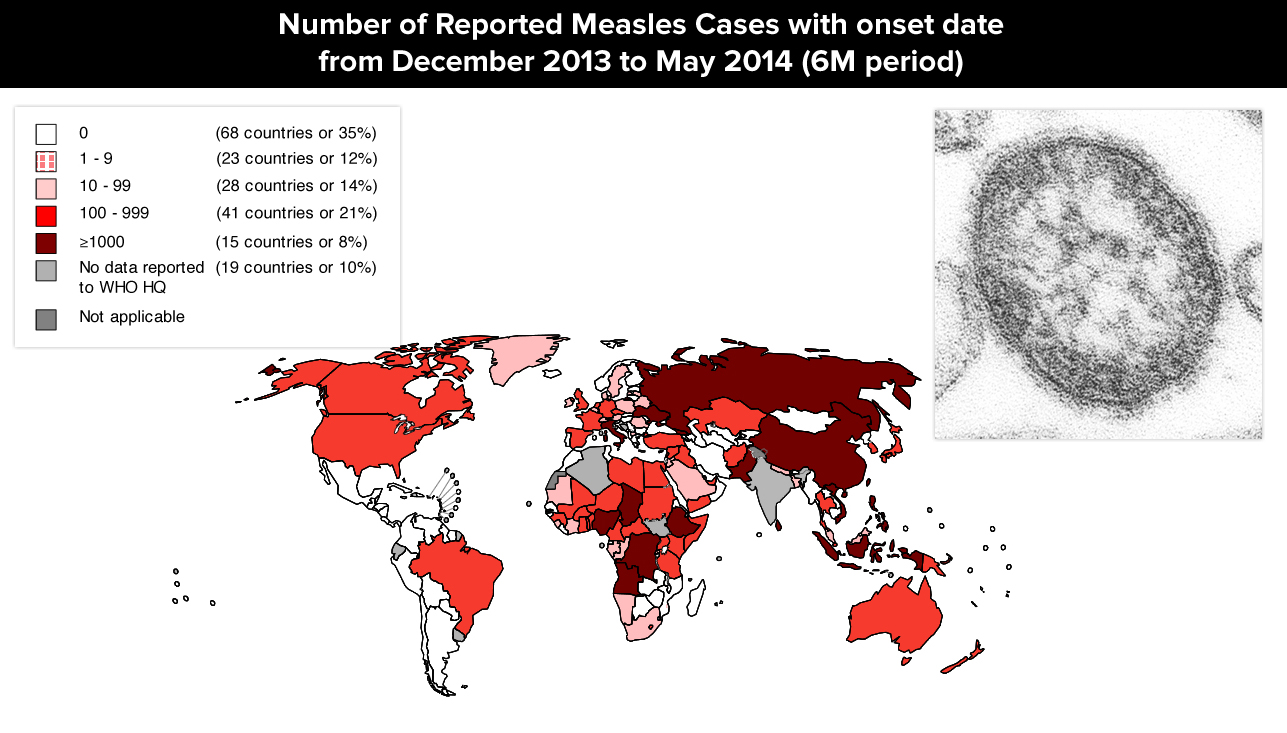

We’ve discussed Measles in previous articles but in light of the current issues Rubeola (measles) is really something to worry about when traveling because if you’re UNimmunized and around it you WILL come down with it – it’s that contagious!

Humans are the only natural hosts of measles virus and transmit it by droplets from the nose or mouth. In the United States, most measles cases result initially from travelers who become infected in endemic areas and then bring the disease back home where it ravages through communities. Worldwide, there are an estimated 20 million cases of measles every year which results in about 164,000 deaths.

It can be a serious illness and require hospitalization in even previously healthy children. Thirty percent of patients develop one or more complications, including pneumonia, which affects about 1 in 20 children and is most often their cause of death. Children younger than 5 years and adults older than 20 years often will get ear infections (10%) which can cause permanent hearing loss, and diarrhea (8%). About 1 child in every 1000 will develop encephalitis, and 1-2 will die of this complication.

WHAT TO DO: Get your measles shot! The measles vaccine is safe, effective and inexpensive and it has been in use for 50 years. No specific antiviral measles therapy exists and supportive care is all that is possible while the disease runs it course.

Polio (poliomyelitis)

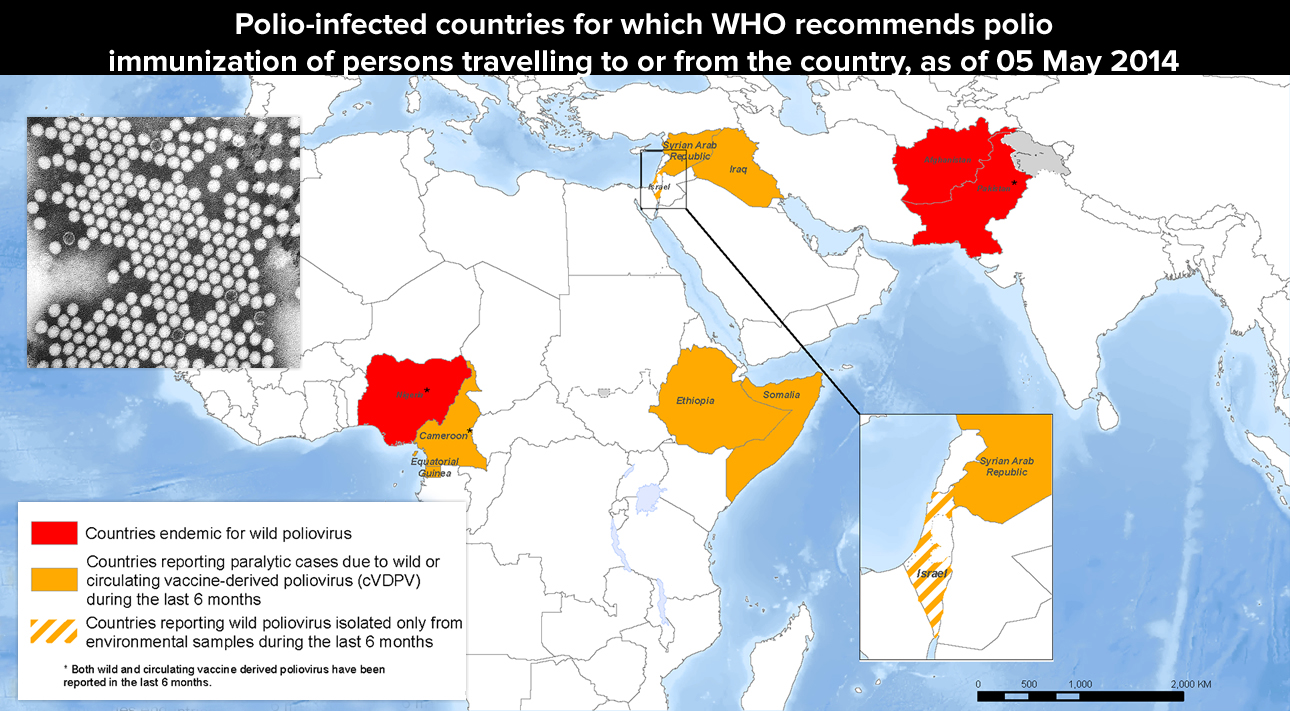

Polio (poliomyelitis) has been the topic of previous articles as well. It is a virus transmitted by the fecal-oral route, attacks mostly children and despite the progress in eradicating it globally, outbreaks still occur in the developed world, usually in groups of unvaccinated people and those who have traveled to endemic regions.

Pretty much like every disease we’ve mentioned so far, there is no cure. There is only symptomatic treatment for fever, headache, neck/back stiffness, limb pain, flu-like symptoms or muscular paralysis anywhere from 6 days to a month after exposure. Five to ten percent of these patients die when the respiratory muscles are affected; almost 1% results in permanent limb paralysis (usually legs).

WHAT TO DO: Infected persons can be without any symptoms themselves but still bring the disease back to any non-immunized member of their family or community. There is only one thing to do: prevent it by obtaining immunizations!

. . .

We’re now half-way through the discussion of diseases we should be concerned about as we travel in the 21st century. Continued on page 2…

3 Posts in Travel Diseases (10TravelDiseases) Series

- Cholera, Bird Flu, TB, Malaria and Yellow Fever – 11 May 2015

- Ebola, MERS, CHIKV, Measles, Polio – 7 May 2015

- 10 Travel Diseases: Intro/Index – 7 May 2015