Joseph Kirsner: Colon Cancer, IBS, Educator, Doctor

It’s one thing to live 102 years and witness two generations of medical advancements and still quite another to be the one who made many of those advances!

Further, it’s even more unusual when the Decagenarian set out to do nothing but “be a good doctor” yet ended up with over 750 articles, 12 books and, get this, TWO lifetime achievement awards—why not he saw almost two lifetimes come and go.

Dr. Joseph B. Kirsner, decagenarian, gastroenterologist

Number 39, in the list of top 50 most influential doctors of all time we are going through, doctor Joseph B. Kirsner was able to witness much of the impact that his own discoveries and innovations in gastroenterology created—in addition to numerous awards and accolades from colleagues, students and patients.

Joseph Barrett Kirsner (1909-2012) – #39

“GI Joe,” “Doctor’s Doctor,” Decagenarian

It was probably coming from an immigrant family to a new country which molded Joseph’s character and social sense. “Selfless,” might be a trite word to describe someone today; but he literally became known the world over for it.

His patients became his best biographers and greatest legacy.

Early Life and Education of Joseph Kirsner

Boston’s east end was a foothold for recent immigrants and that’s where he was born, the first of five children, on September 21st, 1909 to Harris and Ida Kirsner, orthodox Ukrainian Jewish parents who had immigrated through Ellis Island due to increasing prejudicial attacks prior to WWII breaking out.

Into his teens he delivered newspapers, stocked a grocery store and worked as a library clerk using the work ethic given him by his hard-working parents; then graduated valedictorian of Boston English High School in 1927.

He chose a career in medicine “to make them proud” and his father cashed in his life insurance policy to pay for half a years tuition. Joseph had to come up with the other half and began his routine of working one or even two jobs at a time to pay his way through a six-year, combined college and medical school program at Tufts University, living at home and sharing a room with his brother.

“I entered medical school in 1929, the week the stock market crashed,” he said, thinking I’d “go through school as quickly as possible and start earning a living.”

His schooling was marked with his continued efforts to volunteer for opportunities which would enable more learning and greater skills even though they represented extra work; and, his life-long mantra of putting people and patients first solidified into solid personality traits and habits.

An older gentleman he was assigned to care for was near death and without relatives, friends or anyone around him. Joseph returned to him in spare moments and after the days work to befriend him, hold his hand and comfort him so he didn’t die alone.

He graduated from Tufts with a BS and MD near the top of his class in 1933 and moved to Chicago for a two-year internship having been offered free room and board plus a salary of $25 a month.

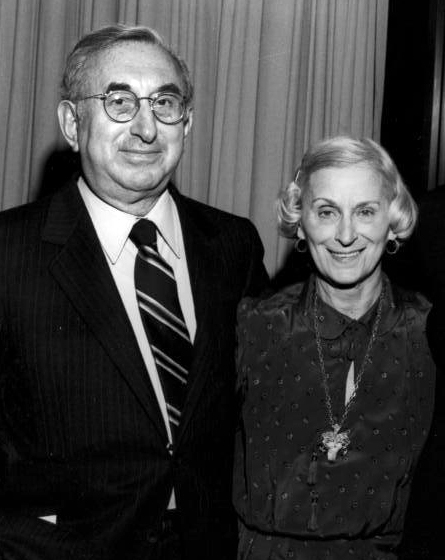

By his second year he had met a young dancer with an ear infection who had been hospitalized, Minnie Schneider, and “fell totally in love with her”; so was married.

She convinced him to enter a subspecialty so he joined the University of Chicago as an assistant professor of medicine to work in the first academic section of gastroenterology with Walter Palmer, the pioneer of the semirigid gastroscope and a refugee from Nazi Germany.

Early Career

At the University of Chicago he immediately began making a name for himself in his own right earning a PhD in the field of ulcer disease and helping found a national GI society.

In 1943 he received word that his grandparents and other relatives had been killed by Hitler’s regime in Europe so enlisted in the Army Medical Corps as a first lieutenant. He was stationed in England during D day and landed on Utah Beach in August 1944.

He entered Paris soon after liberation and was at the Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive in December of 1944.

He helped treat Nazi prisoners of war and wrote about for the first time meeting men full of true hate, despite being carefully cared for and saved by those they had been just trying to harm. He was vehemently told “I hate you” by German officers as he cared for their wounds and relieved their pain.

Following Germany’s surrender on May 7th, 1945 he was consulted about the proper refeeding of holocaust survivors. Some went home after Germany surrendered, most did not.

As he and his hospital battalion sailed through the Panama Canal to serve in the pacific theater of the war his ship’s propeller was damaged delaying their transit. In Japan a bomber struck his hospital killing several and wounding many.

He didn’t understand why he wasn’t in his office at the time as was his custom, and took it as another indication that his vocation was a calling and not merely a job.

He treated those injured in the bombing and was finally discharged as a Major in 1946 with three battle stars; but, continued to advise leaders on how to re-nourish concentration camp victims.

Later Career

Kirsner had begun his professional career having a strong desire to care for patients as individuals and his service in the military only served to intensify his imperative. Over the years, the doctor-patient relationship became the cornerstone of his career.

He became the doctor to King Hassan II of Morocco and for 23 years regularly flew over to attend to him and his family members. He published about 750 scientific papers in his life and wrote the definitive textbook on inflammatory bowel disease which went through 6 editions.

In 1991 the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America honored him with a “lifetime achievement award”—he was 82; then, eleven years later, his continued contributions mounted so high that the foundation could do nothing else but give him the same honor again!

He helped found the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

He “served” at the University of Chicago (UC) for over 70 years giving care one patient at a time. His colleagues called him a “doctor’s doctor” and he had little patience for doctors who lacked the compassion no matter how otherwise competent they were.

At 93 he wrote an article for the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and said: “I cannot condone the diminished sensitivity of physicians to patients, recalling that as candidates for medical school they had professed the strong motivation ‘to help sick people’.”

He was offered a “three-year deferral on his retirement” from the UC and accepted it; then, he kept an office at the college past his 100th birthday dropping in when he “rounded” at 6 AM and leaving notes about patients for his colleagues and students to read when they arrived at eight.

For his 98th birthday he gave a presentation at the university about the history of the UC medical program. On his 100th, he gave a similar talk about the history of gastroenterology.

He never lost his passion for his work (helping patients) and his colleagues knew well that it was “extremely important to see medicine as a profession to which you are called as opposed to something you do and then retire.”

In his mind he hadn’t really “retired” from being a doctor even at 102 when he died of kidney failure on July 7, 2002 in his Chicago home.

Biographic Summary

Joseph Barrett Kirsner was the gastroenterologist who “wrote the book” on GI cancer and IBS

Born: Sept. 21, 1909, Boston Massachusetts

Died: Jul 7th, 2012 (102), Chicago

Education: 1933 Tufts University

Military: Major in US Army during World War II, European and Pacific theaters, rank of Major with three battle stars

Known for: Being a physician’s physician, “GI Joe” in WWII, Colon Cancer, IBS, Medical Educator, Doctor to Kings

Books: More than 750 published articles and 18 books

Parents: Harris and Ida Kirsner, Ukrainian Jewish immigrants to the US.

26 Posts in Top 50 Doctors (top50) Series

- 26 - Carlos Chagas, Chaga's Disease & pneumocystis pneumonia. – 10 Apr 2025

- 27 - Charles D. Kelman - Cataracts – 9 Mar 2023

- 28 - Cicely D. Williams, Kwashiorkor, Breastfeeding, Whistleblower – 21 Jun 2022

- 29 - Dame Cicely Saunders, Hospice – 23 Apr 2018

- 30 - David L. Sackett, Evidence-based Medicine – 2 Apr 2018

- 31 - E. Donnall Thomas & Joseph Murray, Bone Marrow Transplants – 23 Feb 2018

- 32 - Elizabeth Blackwell, women in medicine – 29 Jan 2018

- 33 - Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, stages of grief – 5 Jan 2018

- 34 - Watson & Crick, DNA – 2 Dec 2017

- 35 - Mahmut Gazi Yaşargil, Micro-Surgery – 24 Oct 2017

- 36 - George Papanicolaou, Cytopathology, Cancer – 29 Sep 2017

- 37 - Dr. James Parkinson, Parkinson's Disease – 1 Sep 2017

- 38 - Dr. John Snow, cholera – 20 Aug 2017

- 39 - Dr. Joseph Kirsner, GI Joe – 27 Jul 2017

- 40 - Lawrence (Larry) Einhorn, chemotherapy – 16 Jun 2017

- 41 - Robert Koch, modern bacteriology – 21 Mar 2017

- 42 - Stanley Dudrick, TPN – 28 Feb 2017

- 43 - Stanley Prusiner, neurodegenerative diseases – 25 Jan 2017

- 44 - Victor McKusick, medical genetics – 3 Jan 2017

- 45 - Virginia Apgar, anesthesiology & newborn care – 12 Nov 2016

- 46 - William Harvey, circulation – 12 Oct 2016

- 47 - Zora Janžekovič, burns – 26 Sep 2016

- 48 - Helen Taussig, blue babies – 3 Sep 2016

- 49 - Henry Gray, anatomy – 3 Jul 2016

- 50 - Nikolay Pirogov, field surgery – 11 Jun 2016

- Top 50 Doctors: Intro/Index – 10 Jun 2016