ADHD: Treatment Followup – Lifelong Learning

In order not to break any confidentiality, the name Terry was made up; but, the boy is real. I can still clearly see him… them (two boys and a girl actually), in my minds eye; although, they now look a lot different and have kids of their own.

In fact, I saw them so often I became quite fond of them and worried with their parents when circumstances and choices produced their all-to-common ups and downs of growing up with ADHD.

I used a composite case in that previous post so my descriptions could be more clear and easily conveyed; but, combining them doesn’t make them less corporal or tangible to me.

So, I suppose it is appropriate to follow up for you, about what happened to: “Terry.”

ADHD, Hyperactivity—Followup

What happens to kids with ADHD?

I’ll need to separate out the three children whose stories I used in order for them to make sense to you. Know that I’m being careful to protect confidentialities.

The good thing is that these experiences are SO common to children with ADHD that there are probably thousands of parents for each of them who will swear that I’m describing their own child and family life. Of course, I am not. The things I’ve chosen to include are both specific and general at the same time.

Teri – Delayed effective treatment, Medication only

Teri’s mother was a vegan. And her father sort of went along with it (he didn’t want to have to cook). But Teri didn’t want to have any of “that nonsense“—at least once she reached the age to have a mind of her own… which was early.

In fact, truth be told, that was the real reason her mother agreed to bring Teri to see me… but that’s later in the story.

As an infant and child, it was plain to everyone that Teri was gifted with intelligence. She walked, talked, skipped, understood numbers and did math early and was the most inquisitive person in the family. Beginning about the second grade however, not so much.

Oh, she fidgeted a little but that didn’t seem to be the main issue. She just “daydreamed” all the time. She couldn’t seem to keep her mind on task and rarely finished an assignment due to some distraction or other; and often entered a room having to guess what she was sent there to do.

Between 1st and 6th grade she saw a large number of “practitioners,” largely those referred by her mother’s vegetarian support group, and a lot of money was spent on numerous “alternative medicine” approaches to “ADD”—including numerous lengthy visits with an “eye doctor” who did “therapy” to help her “be more attentive” sometimes four times a week.

Battles with her mom over diet (honestly about everything) reached a climax when she began associating with “less-disciplined” children and trying to fit into their clique. Her caring, but frustrated, teacher advised “you’ve tried every other kind of doctor. Why don’t you try a real pediatrician and see what can be done?”

Even with that encouragement it wasn’t a slam dunk but she finally did agree to come in and I could immediately tell what I was up against. Very long story short, I finally got an agreement to a “blind” trial of meds which included absolutely everyone blind to the medications , and even the use of true placebo pills that I had our pharmacy make up special for me.

She stopped by my office six different times to get a packet of pills, which her dad was responsible to give to her, and “everyone” filled out a rating form every day on her daily activities.

We completed the whole 17-day “test” (even though we didn’t need to) and, not going into the drama, basically Teri’s mom was completely convinced and Teri brought a handful of praise slips from her teachers and papers marked with “A+” and “Great Improvement” and “Keep up the amazing work!”

Unfortunately, the medication was as far as I could get cooperation from her mom. The stigma of “counseling” was out (even though I never called it that). I used my explanations that “pills can’t teach behavior options” but even that didn’t change their minds.

I made an effort to do as much counseling as I could fit in and I did deliberately arrange to see them frequently. Teri was totally convinced and handled her medications on her own. She totally LOVED getting A’s.

She skyrocketed to the top of all her classes, made honors every quarter and was targeting college with advanced placement classes; but, just didn’t break with the crowd she had begun associating with and was married in her senior year of high school with a baby expected shortly after graduation.

She “deferred” college and, last I heard about her, was making a great mother intending to some day get a degree in special education.

Terrey—Medication, Cognitive therapy, Dodged a Bullet

My buddy Terrey came the closest to “being lost” that I’ve ever had a patient go without actually going over the brink and “being lost.”

Hidden in the deepest recesses of the pediatric resident’s doctor’s lounge (where nobody could ever hear us talking) Terrey would have been categorized as a “mother killer”—the type of child who would need 4 or 5 mothers just to keep up with him.

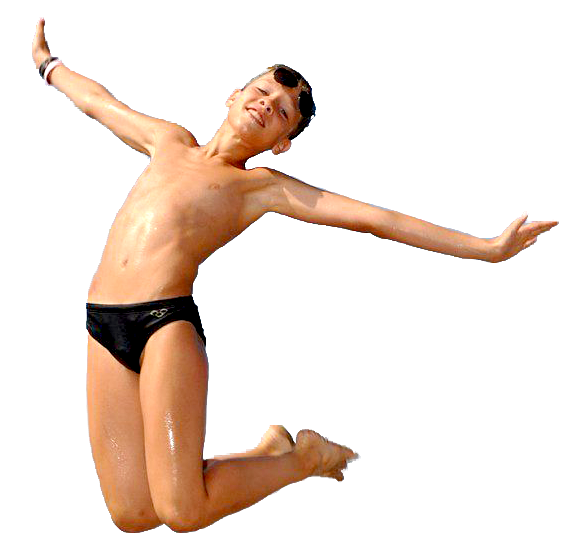

He had the colic, but that wasn’t the worst part—he only ever needed 3 or 4 hours of sleep per night as an infant and not much more than 6 as an older child. To say he was “active” only meant you had never seen him—he acted like he was run by a motor… ALL day!

He did everything early! His mother swore to me he walked at two months! He had no fear and was into absolutely everything. When I first met him he had just become old enough to begin realizing that he was having very few, what you might call, “success experiences” in his day and that he didn’t often make very many people very happy.

One of the things going for him (and it was a really big thing) was that he simply was a really cute kid and literally had a one-in-a-million, engaging smile—which he liked to use.

He was in, on, above, below, over, under and through everything he came in contact with, especially anything mechanical; and often broke it, tripped on it, fell off it, “fixed” it or painted it while he was there.

He fell off everything. An emergency room doctor, whose forte definitely wasn’t children, tried to report them once as “suspicious parents” for abuse, due simply to the history of all his injuries.

His dad saw his behavior as exasperating but not particularly out of normal because he was told he had been that way too. His mother, on the other hand agreed with the teachers when about 4th grade his behavior was unacceptably ruining their class’ ability to even function, in addition to giving Terrey a terrible experience.

Terrey’s diagnosis was clear and proven without a doubt during a diagnostic trial of medications. His teachers were visibly relieved and grateful, he began actually learning and enjoying the school experience—for the most part.

The stigma of his early years’ behavior, however, was hard to live down and he struggled for acceptance when puberty hit in junior high school.

Medications were sometimes “forgotten,” especially when around friends; and one weekend he sneaked out at night with friends which got his parents summoned to the hospital after the car he was riding in hit a boulder in a ditch. He had been drinking with them. He was thirteen.

The next few months we tried some alternative medications and dosing schedules along with a new referral for cognitive therapy. That summer we got him enrolled in a Children’s Summer Treatment Program (Summer Camp)—which, finally, seemed to give him some internalized direction in life: Lacrosse!

The kid seemed to be a “natural.” He loved it. The pace, the skill, the team… the coach. And he was inordinately good at it. Everything clicked and he returned home with intensity in his desire to pursue lacrosse at every opportunity. Which he did.

Even, once they had overcome the shock and concern over the roughness of the sport, his parents could see the pride growing in Terrey and they took pride in how proud he had become, and confident.

We modified his medication regimen downward for his high-sport days and upward for his more academic days—and HE did most of it himself because he recognized the value of each.

The success in Lacrosse transferred into his academic courses. Team skills, focus, follow-through and cooperation are common to each. On his own, Terrey also discovered that music was not only a distraction but wound him up… so he stopped listening to it entirely or the radio. And he never liked to sit through any TV program.

The last I saw him, he had just received offers from three major colleges, both academic and athletic, and could pick whichever he wanted.

Terry – hyperactivity, reading and grandpa

Terry too acted like he was nuclear powered; but, at least he slept well. You would consider him a “good baby” because he slept through the night almost from week two; and he slept the “right amount.”

When he was asleep, he was pretty much comatose; but, when he was awake, everyone in the subdivision knew it and thought that most of the time he clearly was “channeling” Dennis the Menace.

You would also consider him a “daddy’s boy” right from the start because he liked the jittery, rough-and-tumble of his dad more than the “let’s take a nap now sweetheart” of his mother.

For nearly everything his parents were in sync. The only disparity was whether or not Terry’s behavior was “usual and customary.” Dad said: “He’s just being a boy.” Mom said: “I’ve never known any boy like this!” They both agreed on: “He’s a bit hyperactive.”

I met him when he started the 4th grade and the emphasis on cognitive skills became greater than physical skills. The school had done a lot of testing and pronounced him free of learning disabilities—except for those produced by pronounced distractibility and activity; yet, his academic testing was in the lower third of his age range.

He had a very hard breech delivery which, they thought, accounted for his mild delay on all the developmental milestones. Sitting, crawling, walking, talking—all didn’t occur “until the very last possible second in the percentile of ‘normal’,” they said. And he’s always been the smallest in the class. They had decided against the school’s suggestion of keeping him back a year.

It did turn out that Terry’s dad had been diagnosed as “hyperactive” but hadn’t received any treatment, “I just grew out of it,” he said. That is unless you considered the counseling that he had after receiving a below the knee amputation from a car accident as a teen.

He said the counseling helped him a lot by teaching him how to “channel his thoughts and energies into success.”

Because Terry had been small, delayed and a bit uncoordinated, they had decided on swimming lessons around 8 years of age—“which he really likes to do”; and they even put in a pool so he could do it. “It helps him unwind,” his mom said. “And we figured he couldn’t get hurt doing it,” his dad added, “except now he wants a high dive.”

Careful testing did show that he had ADHD, along with its frequently-seen soft neurological signs AND a not-so-frequently-seen exaggerated aversion to reading! That, we all hoped, would turn out to be the result of a reaction to a quite “strict” tutor they had hired during the previous two years and gradually improve.

I’m waxing a bit long on this description. Perhaps it’s because I really liked the kid; although it might have something to do with the fact that only a month after he, his family and teachers had begun responding well to both the results of his medication and cognitive therapy—he ended up in the hospital unconscious with a concussion.

He tripped on the deck of the pool and hit his head on the curb. The ER notified me they had admitted him directly to the neurology service. He was unconscious for 4 days and needed a burr hole in his skull to relieve the pressure before he came back to answer his parents prayers.

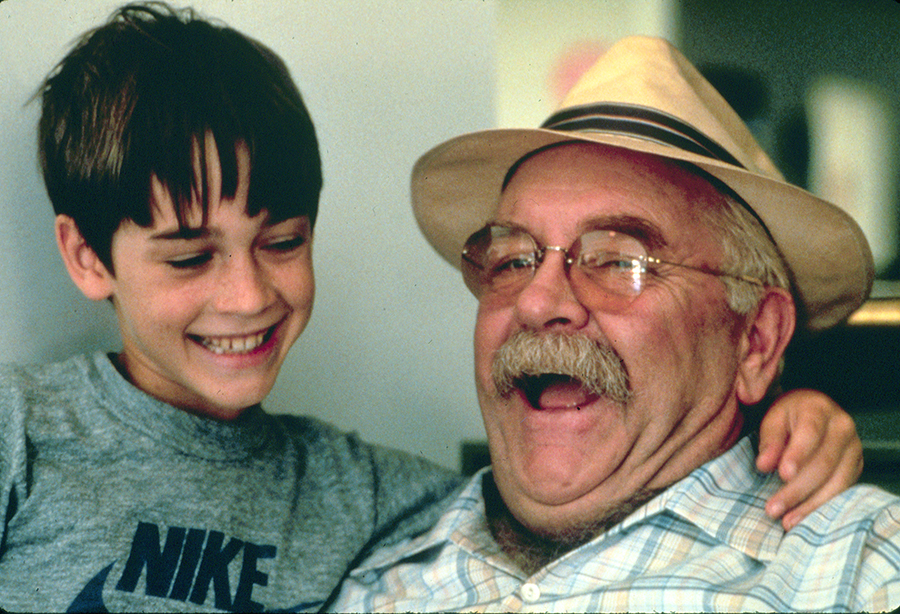

That, was when I met “grandpa.” The man who had helped raise his father had just retired and spent hours, daily in the hospital for the two weeks Terry was there. When they wanted to bring in school work, I declined the request but suggested to grandpa that he find a book that he was interested in as a boy and read it aloud to Terry in short bursts.

That turned out better than I could imagine. Terry couldn’t get enough and I found out why one day when I did rounds. The man “told” that book to the boy sounding exactly like Wilford Brimley. Heck, I tried to round when he would be there just to hear him read too!

The reading habit continued for the month or so he was recovering at home too; until he was ready to go back to school. I know because I saw him there reading when I made some housecalls.

Terry went back to school with a love of the stories found in books; which, slowly turned to an ability to read.

It was no small feat balancing and adjusting all his medication during his hospitalization and rehabilitation; but, I have to say, he did amazingly well. Of course I still saw him regularly after that—and even more regularly beginning around 13 years of age when, still the smallest in the class , the big worry became “am I ever going to grow?”

Terry’s unhappiness about his lack of “growing up” was draining on his mom and dad too. I did all the standard testing and everything pointed to just developmental delay in puberty; but, as time progressed, even I began to doubt. You see, the dilemma for me was about the medication which was helping him succeed in school.

The medication had clearly turned his life around and every time he either forgot to take it or “took a vacation” from it (like during summer vacation or the like) it wasn’t long before even he noticed the difference.

None of the medications cause growth retardation directly. But, because most stimulant medications can decrease appetites, I decreased his dose to the lowest amount which would still work and we eventually gave him medication free weekends.

I switched medications to the type with the lowest amount of known appetite suppression. I saw him every other month, then every month to take measurements looking for signs of growth—worrying that we might need to stop the medication in spite of its benefit. At fourteen he was the size of a healthy 11 or 12 year old.

As we became more concerned, I slowly added more testing to make sure I wasn’t missing anything. It wasn’t until well into his fourteenth year that on one of the exams I was able to point out to him one of the things they had taught him back in sixth grade—puberty.

One of the earliest signs in a boy is testicular growth and his had now reached 2.5 centimeters which put him in Tanner stage II of puberty, meaning that his growth spurt would now start in ernest. And it did!

He hugged me but I saw that his parent’s faces still reserved a lot of doubt. I felt that he should celebrate; so, on that visit, I only half-jokingly told him he should stop by a store on the way home and buy some new clothes… and they did. A whole set, from skin out. One size larger.

The next month’s visit he came wearing them and they fit (only a tiny bit loosely). Another bullet dodged.

The thing about delayed puberty is that: because it is delayed, so is the closing of the growth plate in the bones. Because they don’t close as soon, the eventual height often has a chance to catch up before they stop growing. His graduation photos proved that he had clearly passed the middle of his class in height.

He began working in his fathers company, attended college, married, has children and, last I heard, was primed to take over the company at his dad’s retirement.

Viewing The Other Side Of The Tunnel

What happens to kids with ADHD? To borrow a phrase: It can get better.

Unfortunately not all situations turn out as favorable as these three. We are aware of the relationship between children with ADHD and many types of, let’s say: “non-successes” in life—especially when the legal establishment gets involved.

I think the key to learn from this is that these three received help… a lot of it. They were all able to find success… in something, to varying degrees; BECAUSE they received treatments which others before them had proved that truly worked.

Unfortunately, as I have shown you, it isn’t always easy to find proper diagnosis or treatment for your ADHD child, even within the medical system. Wild schemes and unproven opinions are everywhere. And for whatever reason not all physicians follow evidence-based procedures; or, honestly, care that much about spending the time needed.

Several years ago now, the American Academy of Pediatrics published clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of school-aged children with ADHD. They are the “BEST practices” of physicians successfully treating ADHD which produce the BEST outcomes. I’ll list them so you can seek out physicians who use them.

ADHD Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Primary care clinicians should establish a treatment program that recognizes ADHD as a chronic condition

- Appropriate target outcomes designed in collaboration with the clinician, parents, child and school personnel should guide management

- Stimulant medication and/or behavior therapy as appropriate should be used in the treatment

- If a child has not met the targeted outcomes, clinicians should evaluate the original diagnosis, use all appropriate treatments and consider co-existing conditions; and

- Periodic, systematic follow-up for the child should be done with monitoring directed to target outcomes and adverse effects. Information for monitoring should be gathered from parents, teachers and the child.

14 Posts in ADHD Hyperactivity (hyperactivity) Series

- Hyperactivity & Puberty - Part 2, Issues and Actions – 22 Jan 2019

- Hyperactivity & Puberty - Part 1 – 10 Jan 2019

- The Children - Followup and Outcomes – 26 Mar 2017

- (Link) Don't JUST take my word for it – 23 Feb 2017

- Treatment: Cognitive Training, Medication – 18 Feb 2017

- Treatment: Five Pillars of ADHD Treatment – 4 Feb 2017

- Treatment: How can we know what works? – 29 Jan 2017

- (Video) Sucess in 'Something' Helps – 20 Jan 2017

- The Patient – 15 Jan 2017

- First, the diagnosis – 11 Jan 2017

- Labels and 'Alphabet Soup' – 7 Jan 2017

- Treating ADHD lowers incidence of smoking! – 15 Jun 2014

- Treatments - 'alternative' – 6 Feb 2013

- ADHD Hyperactivity: Intro/Index – 5 Feb 2013

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)