Three Magic Questions of Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding: three questions

Breastfeeding

THREE Questions to Ask

by Gregory A. Barrett, M.D.

Breast feeding is great. Human milk is ideal for humans, cow’s milk for calf’s, mouse milk for mice, and so on. It’s as simple as that. Through thousands of years of trial-and-error nature has been redesigning mother’s milk and has come up with the ideal formula for our babies. I encourage every expectant mother to consider giving it a try.

DON’T Pre-make Ironclad Plan

However, most first-time moms-to-be would be better served not forming an ironclad prenatal plan to “breastfeed for two years” until they’ve actually had an opportunity to get their feet wet. Personally, I would prefer the mother-to-be enter the project with a somewhat lowered set of expectations. It just seems that a more open-minded attitude helps decrease the pressure they put on themselves, and often leads to a better result.

At some point in the breastfeeding process, either sooner or later, the mom will inevitably begin to ask herself how long she should nurse. And to help with this decision I have devised the Three [not-so] “Magic” Questions:

Baby Happy & Well?

1) Is the baby thriving? The answer to this lies in the realm of the pediatrician. No matter how meticulous a mother is at keeping records (i.e. documenting the number and duration of feedings, counting wet diapers, logging bowel movements, etc) she may be misled. The ONLY way to assess the milk supply accurately is a careful physical examination assessing skin color, activity level, and hydration, combined with the baby’s weight. Now, the infant’s weight must be taken in context, because a healthy breast-feeding infant may normally lose up to ten percent of its birth weight in the first five to seven days of life; so new moms should not be allowed to misinterpret the usual weight drop and become prematurely, and inappropriately, discouraged. This is the reason I’m not too much of a fan of home scales, as the weight fluctuates so much on a daily basis parents may overreact panicking needlessly because of a temporary decline. But weight does remain the key tool in evaluating caloric intake. Scales don’t lie. Generally speaking, if the birth weight is re-achieved by two weeks of age you’re off to the races.

Mom Coping?

2) Is breastfeeding compatible with the mother’s schedule? It is a reality of life that many mothers must return to work, and workplaces will differ considerably in how accommodating they are allowing employees to slip away from their desk for twenty minutes of pumping. And then there is the variable of the breast pump itself. Some moms have great success with the device whereas others do not, and the amount of milk the machine can extract does not necessarily correlate well at all with how much the infant is receiving straight from the source. I’ve had mothers who were doing wonderfully nursing, their baby growing and thriving, and then attempted to pump, could scarcely squeeze out a drop, and immediately derived the erroneous conclusion that they didn’t have any milk. At any rate, the time of re-entry into work is a major decision point, and working moms need to look at the practicality of continuing to nurse given their individual circumstance.

Mom Happy?

3) Is the mother enjoying it? This is often overlooked and is, in my opinion, critically important. I feel strongly about this, that if she is breast feeding only out of guilt or some perceived societal expectation it may not be in the infant’s best interest. Babies need happy mothers to be healthy, and if Mom is wincing every time she puts the baby to her breast, is resentful of having the responsibility for all of the feedings, or simply finds it physically repugnant, then nursing may not be in her or her child’s best interest.

Breast Pumping

Before going further I’d like to return to the subject of the breast pump for a moment. The whole concept of its role in nursing has just exploded recently, and I have no idea why. A newborn comes into this world with a precious, albeit brief, spell of hyper-alertness, to be quickly followed by what I refer to as the Rip Van Winkle period, twenty-four hours of basically sleeping, little to no personality, and virtually zero interest in feeding. In spite of this physiologically normal resting phase, the breast pump is invariably brought into the mother’s room immediately and she is encouraged to start using it as soon as possible. First of all, I have no idea what happened to the idea of patiently waiting for the baby to awaken and become interested in feeding naturally, and secondly the use of the pump has a number of unpleasant consequences for both mother and child. It immediately establishes the idea in the minds of many new moms that their baby can’t nurse which, of course, they seem to be able to manage in all other parts of the world where one just waits for them to wake up and become hungry and motivated. And bottle-spoiled can occur quite quickly.

It’s a lot more difficult mechanically to extract milk from the human breast than a bottle, a far greater effort is required, so in a relatively short period of time the child simply won’t put forth the effort to nurse. Then before you know it, the poor mom suddenly has the worst of both worlds, the sole responsibility of pumping combined with all the hassles of preparing, cleaning and storing the bottles and nipples, a scenario which does not bode well for long-term nursing success.

Having said all of that with the right degree of support, technical training, and patience, most babies and mothers do just fine with breastfeeding. But here’s a dirty little secret—it doesn’t work for everyone. For some reason, in spite of excellent coaching and the best of intentions, breastfeeding sometimes fails. Fortunately for those who don’t make a go of it, we are residing in twenty-first century America where one is not forced to choose between human milk and unpasteurized llama’s milk. The commercial formulas are very sophisticated, well tested products mimicking the content and many of the features of breast milk and thus, if necessary, will suffice just fine. So, if the nursing doesn’t pan out don’t beat yourself up, your baby is going to be okay. Remember, there is a whole lot of other important stuff involved in being a parent besides this, so swallow your pride, turn the page, and move on.

Personal Example of Breastfeeding

Rachel, our firstborn, weighed six pounds, fourteen ounces at birth. My wife received excellent teaching and encouragement during her hospital stay and to all appearances seemed to be doing just great with the nursing. That is, so it appeared until we came in for the first checkup at ten days and discovered that our daughter was now thirteen ounces below birth weight. Our pediatrician determined that Rachel’s hydration was still adequate, her jaundice was minimal, and that her mother’s commitment to breastfeeding was unwavering. He reviewed the nursing log and allowed us to stay with the program, planning to recheck our baby in a few days. Unfortunately at the follow-up visit her weight had dropped to five pounds, ten ounces, and our scrawny little girl was beginning to appear pretty dry. He offered us the option to continue nursing, but only under the condition that we begin supplementation with formula to re-hydrate Rachel.

Breastfeeding Specialist NOT League of LaLeche

After arriving home, my wife immediately telephoned the LaLeche League hot line to obtain advice regarding how to mix nursing and the bottle, and the advice she received was surprising.

“Well, the first thing you need to do is to immediately find another pediatrician,” she was curtly informed.

Oops! Wrong answer…!

The vast majority of lactation instructors are great, a pragmatic lot with an amazing collection of tricks and expertise they dispense to help make the experience both enjoyable and successful. The true breast-feeding-evangelists, though, they’re a tough bunch, and they can be dangerous. To them the advantages of nursing are nearly infinite including decreased ear infections, higher intelligence, fewer allergies, solidifying the ozone, putting an end to global warming, balancing the budget, and world peace. Actually, some of that is true, but as for the rest…ehh, it might be a bit of a stretch.

My wife did continue to faithfully nurse Rachel, and with the aid of some judicious use of supplemental formula our daughter did just fine. Three years later along came Keith, nine pounds ten ounces of wriggling demand. She took one look at him and was filled with despair imagining her milk would never be enough for such a monstrosity. But she gave it the good old college try and, wouldn’t you know it, at the two-week checkup he tipped the scales at eleven pounds, two ounces! Which brings up another interesting point—previous breast feeding, even if not particularly successful, primes the pump and generally makes attempts with subsequent children go a whole lot smoother.

Assuming the nursing is progressing well, when a mother asks how long to breast feed the answer should absolutely be for as long as she desires. The single most valuable feeding is the initial one, the protein-rich colostrum, and the most demonstrably worthwhile time is the neonatal period, the first six to eight weeks of life, but there never comes an age where human milk is inferior. The benefits are truly manifest throughout infancy. Thus as stated previously as long as the baby is thriving, the demands of breast feeding are compatible with the mother’s schedule, and both mom and baby are enjoying it, she should nurse away to her heart’s content.

Breastfeeding Opinions on Exam

Once upon a time a simple query about breastfeeding almost cost me dearly. Here’s the story….

To become Board certified in a medical specialty [like pediatrics] these days one must successfully complete a medical residency in a recognized program and then pass a written examination, a test traditionally consisting of silly questions about obscure diseases which a doctor will never see in his or her practice life. Number of questions about diabetes insipidus on my written pediatric boards? Seventeen. Number of patients I have seen with DI in twenty-eight years of practice? One. Get the idea?

If all of that wasn’t enough there used to be an additional piece of hazing called the Oral Boards, and I am not referring to Dentistry here. No, applicants in each specialty, including pediatrics, were required to travel to some exotic locale and face the ritual of being verbally tormented by a bunch of uppity-ups in their field in order to become board-certified. And the Oral Boards were saved for last, usually requiring two years post-residency [practice] and successful completion of the “writtens” (exams) to even become eligible to take the exam. For those of you who have never had endure a test like this, where your whole future rode on the outcome, you cannot possibly imagine how anxiety invoking such a trial can be.

But it was a rite of passage for all of us, a shared misery, and almost everyone comes away from the experience with a favorite Oral Boards story. One that I have always particularly treasured was relayed to me by a Pediatric Infectious Disease attending of mine during medical school. In one of the sessions of the exam the wannabe pediatrician is traditionally flashed a series of pictures and asked specific questions, and on the occasion of his examination he was shown the photograph of a child with a disproportionally large head and short arms and legs.

“So, what do you see here, doctor?” he was asked.

“It’s a dwarf, isn’t it?” speculated my attending.

“Very good,” nodded the examiner. “Okay, now tell me everything you know about dwarves.”

“I already did,” he responded with complete candor.

Tee hee.

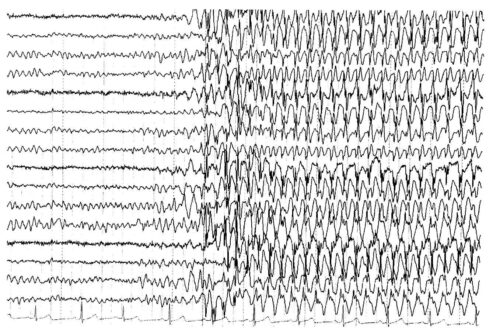

I had a wee bit of trepidation during the “picture part” of my own Orals when I was asked how expert I was at reading EEG’s. The EEG, or electroencephalogram, is the test where electrodes are applied to a person’s head picking up electrical voltage produced by neurons in their brain producing endless rows of waves on a piece of paper, generally considered completely uninterpretable except by a cherished-few specialists in Neurology.

“Oh, lord,” I groaned, wiping the sweat from my forehead with the back of a palsied hand. The examiner smiled and showed me a tracing with a bunch of wiggly lines interrupted about three-fourths of the way across the paper by something which resembled the Richter scale recording of a level 7.2 earthquake. Pointing at the disturbance I took a deep breath and ventured shakily, “Is that a seizure?”

“Right you are!” he winked. “Next…” Whoosh.

My Oral Boards were moving along fairly well with no major disasters, my confidence blossoming as the morning progressed, and as I entered the last room to face my final session, I felt that if I didn’t blow up completely, I was going to survive the ordeal. I sat down across a table from the final hurdle, a short, squat, bitter-looking hematologist from New York City who refused to shake my hand prior to grumpily presenting me with the following scenario: a seventeen-year-old single mom brings in her ten-day-old firstborn infant to the office. The mother is breast feeding. The baby weighed six pounds at birth and on the day of the exam weighs only five pounds, five ounces. Describe how to evaluate this child and how to proceed.

Well, two years of experience in general pediatrics placed this one solidly in my wheelhouse, worlds better suited for me than the interpretation of an electroencephalogram. I dove right in with a clever little differential diagnosis I had invented for failure to thrive, one which I have passed on to generations of medical students and residents: losing weight is the result of either inadequate caloric intake, malabsorption of the ingested nutrients, or an excessive metabolic rate. I proceeded to take a history of the breast feeding, inquired about the presence of vomiting or diarrhea (none), performed an imaginary physical examination of the infant including the vital signs (all normal), and concluded the weight loss was likely due to caloric deprivation. I discussed the pros and cons of supplementation, hooked the mother up with a Lactation Consultant, made a Public Health referral, and arranged to see the baby back in my office in three days.

‘Ahh,’ I thought to myself, settling back in my chair with smug satisfaction. ‘Nailed it. I am pretty sharp, aren’t I? Hand me the Boards!’

“Is there anything else?” my interrogator inquired.

“No, sir,” I smiled. “That would sum up my approach.”

“Anything else you would want to do?”

“I don’t believe so,” I said, becoming a little puzzled.

“Take your time and think for a moment,” he growled, shaking his head irritably.

I paused just for show pretending to reconsider before replying with confidence, “No, that just about does it.”

“Isn’t there anything else you would want to see?” he persisted.

Where was this guy going here? Thinking back, I reviewed my analysis. Had I left anything out? Huh-uh.

“Not that I can think of,” I said slowly.

“Are you sure?” he frowned.

For the life of me I could not think of a thing. Where on earth was he going?

“Yeah, I guess,” I shrugged.

“Wouldn’t you want to watch the mother nurse her baby?” he asked.

“Oh, no, not really,” I chuckled. Was he kidding?

“You wouldn’t?”

“Nope,” I replied, grinning at the idea in spite of myself.

“And why not?”

“I just wouldn’t,” I replied. Uh-oh. The realization began to arrive that this was no joke; he was being completely serious.

“If you don’t mind my asking, what branch of pediatrics are you?”

“I am an office-based general pediatrician.”

“A general pediatrician, and you are trying to tell me that when you have a mother come to your office who is breastfeeding, you don’t routinely ask her to take off her shirt and bra, examine her breasts, and observe her nursing?” he inquired, clearly aghast.

“No.”

“You’re saying you don’t do this?”

“Huh-uh.”

“Would you care to share your reasoning?”

“Well, first of all there’s the modesty factor, and that would apply to both of us, I’m sure. I mean, a lot of new moms might not be too thrilled with disrobing in front of me, you know. Geez, that would be an absolute blushfest for both of us. And then there’s the simple fact that I don’t believe I would learn a whole lot by watching a woman nurse her baby anyway. I generally defer to the Lactation Specialists if I suspect any mechanical problem with the breastfeeding.”

My examiner pushed himself back in his chair and glowered.

“They’re a whole lot better at that stuff than I’ll ever be,” I elaborated for his benefit.

An uncomfortable silence ensued.

“Leave it to the experts,” I offered in a pathetic attempt to lighten the mood.

He stared at me incredulously before finally saying, “I cannot believe what I’m hearing.”

“I’m sorry you feel that way,” I responded as diplomatically as I could.

“So, tell me, when you get back home are you going to change your practice and start asking nursing mothers to show you their breasts?”

“Honestly? No.”

“I think you should.”

“I’m afraid I disagree.”

“I suggest you re-consider that opinion…Doctor.”

“Well…Doctor…that’s just not going to happen.”

He shook his head and glared at me in disgust, never asking another question as we sat across the table from each other jointly awaiting the end of the session, the only sound in the room the clicking of a wall clock. A veritable eternity passed before the gong at long last mercifully sounded. Without uttering a word, I arose and departed to await my fate.

In case you’re wondering I did pass, no thanks to my new best friend. Now, there was one guy who definitely didn’t get breast fed long enough if ever I saw one!

Where Does That Leave Us?

In summary, breastfeeding is GREAT! The advantages of nursing are legion, so go ahead, give it a try. Accept all the expert assistance available to aid in establishing the initial attachment and getting off to a good start. Hopefully your baby will thrive, and most do, if you just show a little patience, persistence, and faith. When nursing works the way it’s supposed to, the experience can be absolutely awesome. It is a wonderful thing you’re doing for your newborn, and also for yourself. Just think, you are feeding your child exactly as nature intended and as countless mothers have done before you for as long as man (or rather, one should say, woman) has strode upon the Earth.

However—be honest about your feelings and do what’s right for you and your baby. Try not to place unnecessary, unrealistic pressure upon yourself. Relax, and see how breast feeding works for YOU. Don’t ever allow stubbornness or guilt to adversely affect your child’s health.

Always remember those Three Magic Questions. I promise, they won’t steer you wrong.

☤

Gregory A. Barrett, M.D.

Gregory A. Barrett, M.D., author of well-known blog “Real Pediatrics,” graduated from the Ohio State University College of Medicine and began practicing at Riverside Pediatrics shortly thereafter.

He is a Clinical Associate Professor at OSU and has received the Distinguished Educator Award by the Ohio State School of Medicine. He received national honors as one of the Best Family Doctors in America by the Ladies Home Journal. He and his wife, Darla Hall, have two children, Rachel and Keith.