Cardiac Arrest in a Child Athlete

Most of you let your children participate in sports so it’s critical that you know this. Bear with me, it’ll be fun – and something you want to talk to the coach about.

A child in cardiac arrest on the playing field is becoming increasingly more common

Sudden Cardiac Arrest

We’ve already learned in previous articles that cardiac arrest in children’s sports, while not really common, IS frequent enough so that at some time in many of your lives you will actually see a case of this while you are watching a sporting event.

And, if you’ve read this blog at all in the past, you’re likely to already know much of this information – follow along to put it all into perspective.

Test Your Understanding

They were dispatched to a local school for a 17-year-old in cardiac arrest after being hit by an elbow in the middle of his chest which dropped him unresponsive to the ground. Paramedics discovered ventricular fibrillation (VF) so defibrillated with 200 Joules, converting him back into sinus rhythm. He is currently awake and alert with vital signs in the expected range. The transmitted ECG showed VF and conversion to normal sinus rhythm after the shock. Their ETA is 10 minutes using lights and siren.

History and Physical Exam Findings

Except for not having a defibrillator on the field (we’ll discuss that some more) the coaches and paramedics did everything right. They had enough training to recognize immediately what had happened and begun life-saving procedures without flailing around screaming and panicking. Paramedics were there in under 5 minutes and able to do cardio-conversion.

Transport took 10 minutes and he regained consciousness but was amnestic and said his chest was tender where he had been hit.

Past Medical History was what you would describe as “clear” to other physicians. No symptoms at all relating to the heart, like palpitations, fainting or exercise intolerance. There was no family history of heart issues either, like structural problems, deaths or arrhythmias. And he didn’t do anything that kids aren’t supposed to do like smoking, drinking, drugs, or doping.

Why do you care about all that? Because there are four main things that can cause what this kid is going through (I’ll list them) and one of them requires that he doesn’t have any indications of the other three.

Physical Exam was what you would describe as “unremarkable” to other physicians. Airway, breathing and circulation are fine with a good blood pressure – even though his heart rate is a bit fast but with a completely normal rhythm and heart sounds (i.e. no murmur). His blood oxygen was on the “lowish” side but went up to 98-99% on oxygen (can’t get higher than 100%).

His mentation and other neurological exam was normal (for a teen) and an unclothed exam revealed only a small forming bruise just above his sternum. The best thing the good exam told you were the things he didn’t have like birth marks, masses and genitalia, limb and body proportion indicators of other known problems.

Test results you describe as “confirming” because even though they didn’t give you a final diagnosis they confirmed what you knew the child was going through. The ECG was a little rapid from his stress but showed normal heart firing. The chest X-ray and “echo” showed no fractures or evidence of any heart abnormalities with good blood flow. All the blood work showed only mild stress related changes but the troponin I level was slightly elevated (0.25 ng/mL – nl < 0.04). CT scan showed mild pulmonary and periportal edema. All pretty expected for a boy whose heart had fibrillated in cardiac arrest and was resuscitated – and a urine drug screen revealed that he was telling the truth.

Have you come to a diagnosis? Here are the possibilities:

Myocardial infarction – death of some heart tissue due to loss of circulation in an area.

Long-QT syndrome – an abnormality of “firing” seen in certain conditions making the heart more vulnerable.

Commotio cordis – heart “firing” abnormality due to a blow to the chest at a critical time in the cardiac cycle.

The information you have so far is pointing to one of the above – possibly two – which is why you admit him to the Pediatric ICU for close monitoring.

The ECG gives you strong indication that it’s not the first three and the good physical exam rules out all but one as well, especially the long-QT. The echo rules out the first one which leaves most of your five fingers pointing at the last: Commotio cordis.

Commotio Cordis

Commotio Cordis: Expectations

The name is Latin for “disturbance of the heart” and is basically a “concussion” of the heart caused by a sudden blow to the chest causing no other injury. But, it’s not just any blow, it has to be one in just the right place and at just the right time.

Commotio cordis is found in “Google” in the general morass about “sudden cardiac death” (SCD) or arrest (SCA) AND IS HIGHLY CONFUSING BECAUSE IT’S NOT THE SAME THING and only minimally applies. Several things cause sudden death and they are not even close to the same thing in adults as children.

Additionally, the several conditions which cause SCD in children all have highly different expectations and outcomes. Resuscitation of heart failure in adults is most often expected to be successful; resuscitation of children is just the opposite – it is not… although some causes are a lot better than others.

Basically, if a child and his/her heart is “normal” before the sudden event the chance of successful resuscitation is better. The reason, you see, is because children most often have cardiac arrest and need resuscitation because of a previously undiagnosed genetic or growth problem of the heart; which, in fact, may then even hinder or prevent resuscitation entirely.

Commotio cordis, on the other hand, begins with a healthy heart which has merely been temporarily “concussed” into a deadly rhythm. Therefore, if the child can be kept alive until the heart can be converted back to a normal rhythm, the expectations should be substantially better.

Commotio Cordis: Description

The Frequency

Commotio cordis is both under-recognized and under-reported, undoubtedly because it’s so uncommon. There is now a US Registry for voluntary reporting (USCCR) but it must scour national papers for its data and the internet for cases; because the registry is as little known as the medical problem.

The last full statistical analysis was done in 2001 when only 180 cases had been documented. At that time 62% occurred in organized, competitive sports; 66% were under 16 years old; and, 80% were male.

The oldest was 20 and struck by a baseball; the youngest was 7 weeks, crying and struck by his frustrated father.

Children and youth are exquisitely more vulnerable because they have less subcutaneous fat and muscle; and their ribs aren’t fully ossified yet so are much more flexible. This makes them more at risk for life-choices which put them in harms way of baseballs, footballs, hockey pucks, elbows, fists and hard earth objects they fall on.

The Blow

After someone noticed a pattern forming in 1930, a fair amount of research ensued and found that impacts were nearly always of low energy and velocity. Collapse was usually immediate but in almost half followed a short delay.

Some researchers found that the force transmitted to the heart was directly related to the hardness of the object; and others discovered baseballs can cause ventricular fibrillation at speeds between 25 and 30 miles per hour.

Over 50 mph likelihood of VF decreases and heart bruising increases.

The Location

Also, in order to trigger VF, the impact must be directly over the heart – over or just to the left of the sternum.

Hitting on the center of the heart triggered VF in 30% of the cases. Hitting over the base (lowest point directly down) produced it 13% and at the apex (tip of the heart) 4% of the time.

The Time

Additionally, if the impact doesn’t occur at a specific time during the victims cardiac cycle it will only cause tissue damage and not VF.

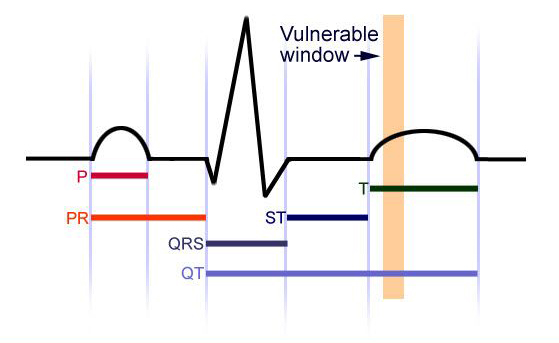

The graphic above shows the tiny 10-30 millisecond brown band of time during the heartbeat where fibrillation can be triggered. Before or after that – the bullet was dodged!

That specific time is right at the beginning of when the heart repolarizes itself after squeezing getting ready to do it again.

It’s just like pushing your child on a swing. All you need to do is gently give an extra “oomph” right when they begin to go downward and you generate an extra high swing that, if you’re not careful, can send them flying.

Commotio Cordis: Treatment and Prevention

As you are saying “adios” the boy asks you: “can I still play baseball?” You knew this question was coming but you need to catch up a bit on the literature so you tell him: “You can go to the game as a spectator but take it easy for a week without playing until you see me in the office. By then I’ll figure out if there’s any further testing we need to do and how we can keep you safe enough to do sports. We’ll talk about it when I see you.”

…

That’s also when you and I will finish our discussion about Commotio Cordis: part two, it’s treatment and prevention. And talk about what you can do to keep children “safe” in this “lightening striking twice” type of situation.

5 Posts in Child Cardiac Arrest (cardiacarrest) Series

- Commotio Cordis: Prevention and Return to Play – 9 Sep 2016

- Commotio Cordis: Treatment and Prevention – 26 Aug 2016

- Sudden cardiac arrest - case – 7 Aug 2016

- Sudden cardiac death – 26 Jul 2016

- Sudden Cardiac Arrest in a Child: Intro/Index – 25 Jul 2016

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)