Children’s Contact Sports – A “Re-Think” Needed

It seems as though we are in a bit of a trend here with posts about children’s contact sports. It has to do with the fact that I’ve needed to give out advice to parents for years with very little in the way of scientific literature to go on and now we seem to be swimming with research studies.

It’s terrible that it happens this way but I’m sure the new found scientific interest has a lot to do with several high placed deaths of star athletes and the ensuing litigatory frenzy.

With the suicide death of NFL star Junior Seau being laid at the feet of repeated brain trauma during practice and games, you would think that there would be little room for argument that some drastic change was needed in the whole sport, let alone children’s sports.

But, pretty much like like the Dementia Pugilistica of boxing that damaged the lives of Ellis, Patterson, Chacon, Quarry (2), Young, Benitez, Griffith, Pep, Roach, Robinson, Conn, Frazier, Zivic, Taylor, Johansson and Clay (Ali) – and probably thousands of others not important enough to make headlines – once the funeral is over it’s pretty much back to status as usual.

The problem is that this is not just about the informed-decision of adult sports stars, this is about our kids. Children relying on the maturity and intellect of the adults in their lives for direction.

We’ve seen in previous articles that there are about 2,000 ER visits a week in the US during football season for game-related injuries. We’ve seen that there are even four deaths a year in the US due to child/adolescent football from sand-lot to college.

We’ve already seen that there is incontrovertible evidence that our current criteria for diagnosing a concussion (and thereby removing a damaged child athlete from play) is completely inadequate to identify nearly fifty percent (half) of children with impairment! There is no court-side sign or symptom that would indicate a need to pull these players out of a practice or game, so they just keep getting hit.

We’ve found that, especially linemen and line-backers can be blind-sided with up to 100 G’s of force to the head (space shuttle astronauts receive under 10 Gs).

On The Track To Good Sense

In October 2006, Zackery Lystedt suffered a severe brain injury because no one recognized the signs and symptoms associated with a sports concussion, Lystedt continued to play and later collapsed with a life-threatening injury.

In October 2006, Zackery Lystedt suffered a severe brain injury because no one recognized the signs and symptoms associated with a sports concussion, Lystedt continued to play and later collapsed with a life-threatening injury.

In children’s contact sports it is absolutely critical to identify traumatic brain injury as soon as it occurs in order to avoid the “second injury” syndrome where an incompletely recovered brain suffers catastrophic collapse from a minor second injury – as happened to Zackery.

In May 2009, Washington State passed the Zackery Lystedt Law, the nation’s toughest return-to-play law. It requires medical clearance of youth athletes under the age of 18 SUSPECTED of sustaining a concussion before they can be sent back into a game, practice, or training.

SUSPECTED is the operative word here because a severely injured child may not have slurred speech, dizziness, unconsciousness or other “hard signs” of what we have, in the past, called a “concussion.” The severity and mechanisms of impact should be all that’s needed; but, how does a field-side physician do that with the coaches and even parents all screaming for him to “not be a wuss”?

Finding The Right Decision

After Seau’s death, Kurt Warner, the former quarterback who led the St. Louis Rams and Arizona Cardinals to the Super Bowl, said he wouldn’t permit his youngsters to play contact football. Bart Scott, a linebacker with the New York Jets, echoed Warner. Others joined the chorus.

Trainers and coaches scrambled to make sense of the public concern as well as attempt to bring some rationality into their coaching and training practices. Neurologists and neurosurgeons were hired to not only advise but be on the coaches bench during games.

Several initial changes were made to pro procedures and policies but what about the kids? Speaking of contact sports for children, University of Maine football coach Jack Cosgrove agreed that there’s no need for a player to play tackle football before he’s 14.

Where did he come up with that number? Who knows, I sure don’t. Fourteen is junior-high <-> high-school (ninth grade) in the US, a natural “dividing line” so-to-speak. Is that where it came from? I would hope that there would have been a more scientific approach than that.

Where did he come up with that number? Who knows, I sure don’t. Fourteen is junior-high <-> high-school (ninth grade) in the US, a natural “dividing line” so-to-speak. Is that where it came from? I would hope that there would have been a more scientific approach than that.

Why? Because, what research is showing us is that better helmets don’t prevent concussions. Better padding doesn’t do it. Absolutely the only way to lose the risk is modification of the rules. The only way to avoid concussions in children, during the time that the brain is most vulnerable, is to prohibit tackling (or other high-G-force activities) until at least age 14 – perhaps even longer, because the jury is still out on this particular topic.

Absolute Lunacy

During a Pop Warner (children’s community league) football game in Massachusetts. FIVE players on a losing team from the Worcester area suffered concussions during the lopsided 52-0 game. Both coaches were suspended and the referees have been banned – AFTER THE GAME.

Where was the outcry or rationality that would have stopped the travesty long before the fifth brain injury? Well, you’ve been to “little league” games haven’t you? Craziness happens. Otherwise rational adults just stop thinking.

Pro Football Players’ Sons

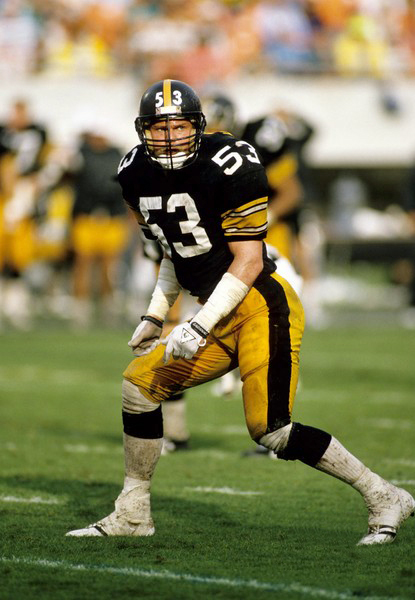

Brian Hinkle is but one of many professional football players faced with parenting decisions involving their own son’s participation in contact sports. A twelve-season player for the Steelers, his son is only seven and is too young for tackle football yet; but he is trying hard not to “over-react” to every possible danger when he makes decisions for his son.

Brian Hinkle is but one of many professional football players faced with parenting decisions involving their own son’s participation in contact sports. A twelve-season player for the Steelers, his son is only seven and is too young for tackle football yet; but he is trying hard not to “over-react” to every possible danger when he makes decisions for his son.

“[You have to realize that ] it’s not just concussions. Football is a violent sport,” Hinkle says. “There’s a lot of issues with football, period. You’ve got to figure, is it worth your son playing, he might blow a knee out, or get an ankle injury, let alone a concussion.”

He has decided to do what his own parents did with him: No tackle football until the 9th grade. That bit of parenting seemed to work for him and his career. For now his son is enjoying playing flag football in Pittsburg.

Recent “Sporting News” Survey

Perhaps it’s the three concussions and six surgeries that gives Hinkle his rational approach to decision making on the subject. Although he and a couple other pro-football fathers did have a bit of difficulty fitting his own opinion into the “FORCED CHOICE,” so-called “survey” conduced recently by Sporting News.

He and 113 other former NFL players were “surveyed” recently by a magazine trying to get a story using the “concussion” angle. In the typical “get the story without much effort” attitude of news agencies they asked the question: “When it comes to football with your kids, grandkids and other relatives, would you:”

The only three choices they gave the players were: “a) encourage them to play, b) discourage them from playing or; c) allow them to decide but describe the risks (?!)”

Pure Clap-trap

I’m sure they were trying to obtain as “sensational” of an answer that they could build into their children’s contact sports story without appearing too biased; but, I mean… Really?! “Allow them to decide by describing the risks?” Were they that rushed that they couldn’t spend even a minutes thought on the matter?

“Kids and grandkids” was clearly the question – CHILDREN. Since when, in a rational society, can a child give informed consent? Does any intelligent parent give their five-year-old a choice about sitting in a car seat?

In our society our kids can’t give sexual consent until they’re 18. They can’t make a decision to drink alcohol until they’re 21. There are age limits to when they can vote or join the service or take out loans or buy guns or drive cars!

Would a parent in their right mind give a 14 year old a “choice” to use tobacco because all their friends are using it no matter how much “information” you gave them?

Frankly, that’s the stupidest thing I’ve heard all year! But, how did the retired pro football players take the bait? Unbelievably, twenty-seven said they would encourage their kids to play. Five said they would discourage their kids from playing. Seventy-two said they would allow their kids to decide but describe the risks.

Are we truly that weak or naïve as parents that we are willing to shunt a tough, unpopular decision to a kid? Even if it meant looking “un-tough” for a sports magazine?

Are we truly that weak or naïve as parents that we are willing to shunt a tough, unpopular decision to a kid? Even if it meant looking “un-tough” for a sports magazine?

I vividly remember a television commercial from my childhood where the advertisers capitalized on the public’s perception of how mentally dense football players were by using a close-up of a Neanderthal-looking football player stating, in a dimwitted, halting speech: “buy one get one free.”

This, perhaps, even more clearly identifies the irrationality of decision making in sports where “looking tough” is more important than “being smart” – but even at the expense of your own kids?

The Best Answer

In some fairness there was no “d) none of the above” option given. But, Hinkle and a couple of others didn’t fall for it. He didn’t circle any of the answers. He wrote, “not sure” in the margin. Seven of his fellow retirees circled “a” and “c” and two more circled “b” and “c.”

Obviously I wasn’t one of those whose “opinion” the magazine thought was important; but, I would have simply written “this is a STUPID question!” Ten out of 114, only less than 10% were smart enough not to fall for the either “stupid” or “hidden agenda” type question.

We (scientists) may have been slow off the starting blocks in trying to obtain real injury data. And, there may not be nearly enough adequate information to make all the decisions needed. And, there may not be a lot of clear answers or guidelines. BUT, THIS IS CLEARLY NOT THE CHILDS RESPONSIBILITY TO DECIDE!

The best news of all, to me at least, is that Brian may luck out and have the best solution of all – his son likes baseball better and might not want to play tackle football anyway.

[Thomas M. Talavage (et.al.). Functionally-Detected Cognitive Impairment in High School Football Players Without Clinically-Diagnosed Concussion. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2010; http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/neu.2010.1512]