Disease Outbreaks and Epidemics in History

Over 15 years ago I wrote an article bemoaning the fact that we were into a generation where even grandmas, the traditional mentor of first-time parents, hadn’t seen a case of measles; and what a loss of valuable information passing across generations.

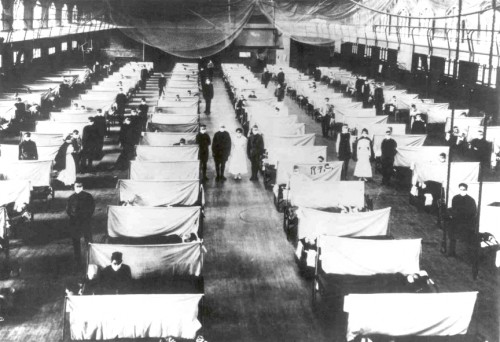

Makeshift hospital ward during flu pandemic

At the time even I had seen less than 25 cases of measles in my whole practice and most of those were refuge children from Vietnam.

Today, thanks to a few of those in that perspective-deficient generation of parents, the disease once largely eradicated is returning and we’ve now even got practicing physicians trying to diagnose and care for diseases they’ve never seen either!

In this article I thought I’d pass on a little test on the topic of world epidemics I took recently along with many other physicians. A real eye opener which serves to put a lot of things in perspective about what we are risking if we let these diseases get a foothold again.

Let’s see how well YOU do.

Historical Outbreaks and Epidemics

QUESTION ONE: Continent to continent spread of an infectious disease was first documented for: A) The Plague of Athens, B) Smallpox in the new world, C) The Plague of Justinian, D) The Sixth Plague of Egypt or E) the Pestilence of Mycenae?

Entire culture disrupted

Smallpox killed so many Native Americans and early settlers that it was the obvious answer to almost 40% of physicians, and I’m sure you remember it from your American History classes too. But that is wrong.

In 430 BC the historian Thucydides came down with an epidemic disease so bad that it killed over 33% of Athens including its ruler, Pericles, and pretty much wiped out their entire army. Fortunately Thucydides survived to write about it in the hopes that it could be prevented in the future.

The fever, cough, diarrhea, pustules and infections of the fingers and toes sort of sounds like either typhus or typhoid fever to us in the 21st century; but, there is no real way to tell for certain. Sanitation, crowding and hygiene afford both of those diseases to spread rampantly.

Mother and infant during smallpox epidemic

Mother and infant during smallpox epidemicSo, the “final answer” is The Plague of Athens which only garnered 18% of the guesses from physicians. The plague began in Ethiopia, traveled to Libya and Egypt then arrived in a port city (Piraeus) before decimating Athens – marking the end of the “golden age.”

QUESTION TWO: Resistance to the plague of Malaria is conferred on those with which genetic condition? A) Cystic fibrosis, B) Hemophilia, C) Tay-Sachs disease, D) Thalassemia/Sickle Cell Anemia or E) None of the above?

A back door blessing?

I thought for sure most physicians would easily get this but only a bare 47% knew that it was the genetic blood disease Thalassemia which inhibits the mosquito-borne parasite (Plasmodium falciparum) from getting a foot-hold.

Both thalassemia and sickle cell cause production of defective hemoglobin and anemia which apparently deters the parasite allowing survival of those people during epidemics of malaria in the Mediterranean and southern Asia.

The parasite probably originated in gorillas spreading to humans around ponds and ditches where mosquitoes could breed, become infected and spread it around as they traveled. A study in Papua New Guinea showed those with thalassemia were 60% less likely to suffer from severe malaria.

The devastation that Malaria wreaks on a population’s survival has spawned at least four other genetic adaptations that I can think of in addition to the two mentioned. It’s a bad disease to get started in a community.

QUESTION THREE: Epidemics of which disease afflicted indigenous Americans before Columbus (1492)? A)Dengue fever, B) Yellow Fever, C) Chagas disease, D) Cholera or E) Babesiosis?

Epidemics before Columbus

Kissing bug responsible for chaga’s disease

Kissing bug responsible for chaga’s diseaseDisappointingly, only 29% “guessed” the right disease, Chagas, and almost as many thought Cholera was the killer (it largely came on the scene after Columbus). Heck, I even had to look up Babesiosis!

The “balance of trade” between the peoples “discovering” the new world and those “being discovered” was terribly lopsided as far as exchanging epidemic diseases was concerned. Native Americans were infected with smallpox, measles, mumps, typhoid, typhus, influenza, diphtheria, and scarlet fever among others by the new “tourists.” All they had to give back in return was Chagas disease, Carrión disease and possibly syphilis. [It’s still being debated whether the disease was already in Europe before it was first recorded in 1495 or if Columbus brought it back with him.]

Chagas disease is a severe protozoan infection transmitted by the kissing bug, or Triatoma infestans. It still causes misery today and is difficult to treat, let alone diagnose for those who haven’t seen it.

QUESTION FOUR: Do you remember Mary Mallon? What role did she play in the history of infectious diseases. A) Assistant to Jonas Salk suggesting the first use of killed polio virus for a vaccine (1952), B) Zaire researcher describing Ebola virus (1976), C) Identified as the first known carrier of Salmonella typhi who wasn’t ill (1908), D) first woman certified in infectious disease by the ABIM (1974) or E) Entamoeba mallona named after her when she died of dysentery during the Irish Potato Famine (1846)?

Disease carrier not ill

Finally, a question where a bare majority (59%) squeaked out the correct answer – a carrier of Typhoid Fever.

At the turn of the 20th century upper-crust families in New York were contracting typhoid fever one after another. A private researcher, George Soper, was hired by one of the wealthy families who discovered that 7 of the 8 families so struck had hired a woman named Mary Mallon as their cook.

Of course she was upset at the accusations because she was perfectly healthy and refused to give stool, blood or urine samples. Only after the police forcibly took her into custody was she found to be the first confirmed asymptomatic carrier of Salmonella typhi.

It was an author in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) who, in 1908, dubbed her as “typhoid Mary.” She was quarantined until 1910 when she pledged to switch professions.

Whether she couldn’t or wouldn’t find other work, she changed her name, eluded Soper and spread typhoid fever for 5 more years until authorities caught her again and she was quarantined for the rest of her life.

Massive hospital ward full of iron lungs

Massive hospital ward full of iron lungsQUESTION FIVE: Which of these pandemics had the highest estimated death toll? A) The Antonine Plague, B) The Spanish Flu, C) The Plague of Justinian, D) The Black Death or E) The Modern Plague.

Top epidemic killer

Incredibly, to me at least, a mere 50% of the medical types who took the quiz with me knew that the “Black Death” – “THE Plague,” Yersinia pestis – was and still is the largest killer of all time. Almost all the rest of the takers thought it was the Spanish Flu, the next largest killer.

The Black Death, peaking between 1348 and 1350, killed 75-200 million people… in other words, something like a fifth of the people then living in the world, including half the population of Europe.

In 1334, it swept through China along trade routes killing whole villages along the way. The bacterium Yersinia pestis sometimes caused a form of septicemia that darkened extremities, giving rise to the name “Black Death.”

The populations of China and Europe dropped by about one half by the end of the century. Estimates of the worldwide death toll range from 75 million to 200 million.

By comparison, historians have estimated death tolls for the Spanish Flu (1918-1919) at 50-100 million, the Plague of Justinian (541-542 AD) at 25-100 million, the Modern (or Third) Plague (1855-1959) at 10-12 million, and the Antonine Plague (165-180 AD) at 5 million.

QUESTION SIX: What parasite has been blamed for killing Arctic explorers? A) Tapeworm, B) Naegleria, C) Trichinella, D) Schistosoma or E) Whipworm?

Larvae in animals

Attempting to reach the North Pole in a hydrogen balloon, Swedish explorer S. A. Andrée crashed with his two companions after only 2 days. Their bodies weren’t found until 37 years later in 1930 along the route they were using to hike back across the ice.

It was concluded, from a polar bear carcass at their last camp site, that they had died from Trichinella spiralis (trichinosis) a common infliction of many animals including pork. The theory has also extended to many who died in other expeditions such as the Englich explorer Henry Hudson in 1611 and the crew of the Danish ship Unicorn in 1619.