Elizabeth Blackwell

We’ve been following a list of the 50 most influential physicians in history compiled by a medical magazine and have reached number 32 with Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell.

A lot has been written about her, I suppose mostly due to the fact that she was the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. No small feat; but, it’s difficult to describe how to call it: serendipity? Chance? Accidental? Stubbornness? Tenacity? Luck?

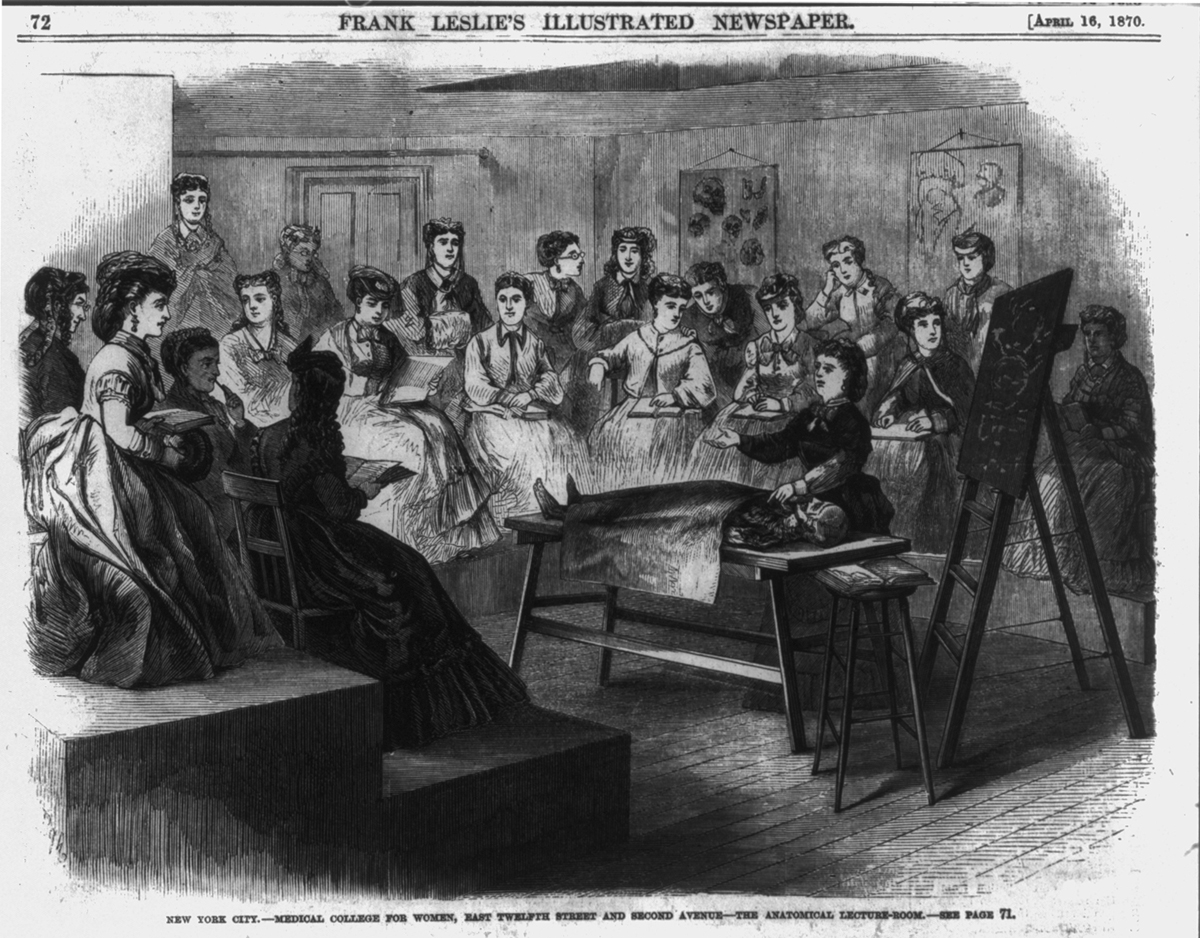

Elizabeth Blackwell and her dispensary

Elizabeth’s upbringing taught her the “possibilities” of life and gave her a taste for something more than a merely “adequate” life. Her situation also gave her the “will” to demand that it happen.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821—1910) – #32

Anything But Accidental, First U.S. Woman MD

Elizabeth Blackwell was born in Bristol, England in 1821, to Hannah Lane and Samuel Blackwell, a well-to-do sugar refiner; therefore, she was raised in a setting of privilege with a governess and multiple private tutors to supplement her intellectual development. And thus she grew up rather socially isolated from all but her family.

Early Life and Education of Elizabeth Blackwell

For financial reasons, as well as because her father was determined to go over to America abolish slavery, in 1832 the family moved to New York—she was eleven. Her father died in 1938 but his children continued their life of privilege and campaigned for women’s rights and the anti-slavery movement.

She studied history and metaphysics and claimed that she was “abhorred by everything connected with the body [especially] medical books.” She went into teaching, a field “more suitable for a woman” and was doing that when a friend dying of cancer told her that she would have been “spared her worst suffering if only her doctor had been a woman.”

From then on she changed her mind and decided to study medicine. She didn’t know how to go about it but when told that she hadn’t yet prepared academically for it, that it was expensive and that such education wasn’t available to women, she got her back up and decided that nobody was going to tell her she couldn’t (least of all men) and “no one was going to stop me.”

She “convinced” two physician friends to let her “read medicine” with them for a year in their office and applied to ALL the medical schools in New York and Philadelphia as well as 12 more in the northeast states.

She was turned down by all of them. Except that the Geneva Medical College in western New York State decided they would “show her” by saying that they would “put it to a vote” of the student body; who they knew very well would vote no. However, literally as a joke, enough voted “yes” that she “accidentally” gained admittance over clear reluctance of most students and faculty.

That was in 1847 before medical education had really gained a foundation and two years later (1849) she became the first woman with an M.D. degree from an American medical school. She then promptly went to work in clinics in London and Paris for two years.

Studying midwifery in France she contracted “purulent opthalmia” from a young patient and lost sight in one eye before she returned to New York in 1851.

Later life:

Once back in the U.S. her arrogant manner and temper were off-putting to most of her peers so she was refused several positions she applied for; but, she did eventually open her own small clinic with a friend, Dr Marie Zakrzewska, and her sister Emily who had by then become the third woman in the US to get a medical degree.

The tiny, part-time clinic that they started eventually grew into an actual “medical school,” the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, to which women from all over flocked when they couldn’t be accepted at schools elsewhere.

She never gave up her campaigning for social reform issues and the article in Wikipedia is lengthy with her “ins and outs” between the US and Europe as well as her various falling’s out with her associates which eventually ended up with her living in England.

She adopted an Irish orphan, Kitty Barry, out of loneliness, a feeling of obligation and a need for domestic help. Barry was brought up as a half-servant/half-daughter and became Blackwell’s companion in her later years.

Blackwell’s campaigning for women’s rights and acceptance into academia and the workplace seemed never to trickle down to Kitty whom she never permitted to develop her own interests. She also made no effort to introduce Barry to young men or women of her own age.

Neither Elizabeth or any of her four sisters ever married. Elizabeth wrote that she thought “courtship games were foolish” and that she had turned down attempts at courtship in Kentucky—largely feeling that the men were “only about a sixth” her equal “which would not do.”

In 1895 she published her autobiography which didn’t sell well, only 500 copies. She made one last visit to the United States in 1906 where she took her first and last car ride.

In 1907 she fell down a flight of stairs while holidaying in Scotland leaving her almost completely mentally and physically disabled. On 31 May 1910, she suffered a stroke at her home in Hastings, Sussex and succumbed to paralysis. Her ashes were buried in the graveyard of St Munn’s Parish Church, Kilmun.

Biographic Summary

Elizabeth Blackwell was the first woman to gain an MD degree from an American medical school

Born: 1821 in Bristol England

Died: 1910 in New York

Education: Geneva Medical School, New York

Known for: Being the first woman to gain an M.D. from an American medical school, helping found a women’s medical school

Books: Medicine as a Profession For Women, in 1860

Parents: Hannah Lane and Samuel Blackwell

26 Posts in Top 50 Doctors (top50) Series

- 26 - Carlos Chagas, Chaga's Disease & pneumocystis pneumonia. – 10 Apr 2025

- 27 - Charles D. Kelman - Cataracts – 9 Mar 2023

- 28 - Cicely D. Williams, Kwashiorkor, Breastfeeding, Whistleblower – 21 Jun 2022

- 29 - Dame Cicely Saunders, Hospice – 23 Apr 2018

- 30 - David L. Sackett, Evidence-based Medicine – 2 Apr 2018

- 31 - E. Donnall Thomas & Joseph Murray, Bone Marrow Transplants – 23 Feb 2018

- 32 - Elizabeth Blackwell, women in medicine – 29 Jan 2018

- 33 - Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, stages of grief – 5 Jan 2018

- 34 - Watson & Crick, DNA – 2 Dec 2017

- 35 - Mahmut Gazi Yaşargil, Micro-Surgery – 24 Oct 2017

- 36 - George Papanicolaou, Cytopathology, Cancer – 29 Sep 2017

- 37 - Dr. James Parkinson, Parkinson's Disease – 1 Sep 2017

- 38 - Dr. John Snow, cholera – 20 Aug 2017

- 39 - Dr. Joseph Kirsner, GI Joe – 27 Jul 2017

- 40 - Lawrence (Larry) Einhorn, chemotherapy – 16 Jun 2017

- 41 - Robert Koch, modern bacteriology – 21 Mar 2017

- 42 - Stanley Dudrick, TPN – 28 Feb 2017

- 43 - Stanley Prusiner, neurodegenerative diseases – 25 Jan 2017

- 44 - Victor McKusick, medical genetics – 3 Jan 2017

- 45 - Virginia Apgar, anesthesiology & newborn care – 12 Nov 2016

- 46 - William Harvey, circulation – 12 Oct 2016

- 47 - Zora Janžekovič, burns – 26 Sep 2016

- 48 - Helen Taussig, blue babies – 3 Sep 2016

- 49 - Henry Gray, anatomy – 3 Jul 2016

- 50 - Nikolay Pirogov, field surgery – 11 Jun 2016

- Top 50 Doctors: Intro/Index – 10 Jun 2016