Intussusception In Children – Diagnosis and Treatment

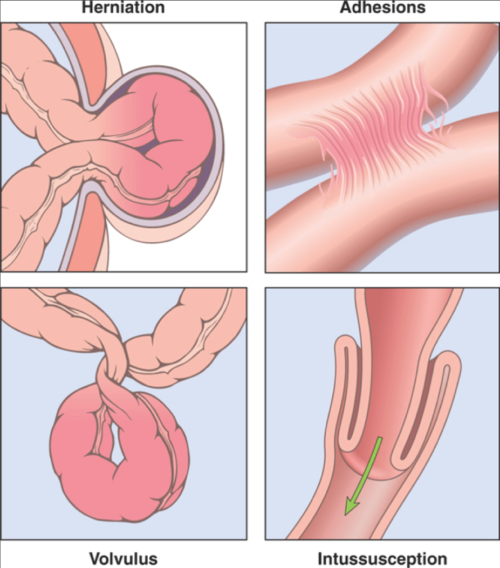

There are four causes of bowel obstruction in children: Herniation, Adhesions, Volvulus and Intussusception. I’ll describe the four (shown in photo) but expand a bit on intussusception—which is the topic of this article.

A bowel obstruction, inability of food to pass completely through the intestinal system unimpeded, can occur at any age and there are many causes; but, time has shown us that we can narrow the most probable causes down a bit based upon age.

Four causes of bowel obstruction in children: hernia, adhesion, volvulus and intussusception

Bowel Obstruction in Children

As you probably already know, what is considered the GI tract runs from the mouth, through the esophagus into the stomach, into the small bowel, into the large bowel and exits out the rectum.

At any point along the “tube” something can happen which blocks the opening and that is called an obstruction. When that happens, all food begins to back up and distend behind the obstruction while everything empties and deflates in front of it. That enables a decent “guess” about where and what the obstruction is by taking a simple x-ray.

If a baby is born with an opening in the abdominal wall, a hernia, then an increase in pressure inside the abdomen can cause a part of the bowel to slip out into the hernia sack (shown). Of course, out there the bowel is “squished” and food cannot pass through. Diagnosis usually isn’t all that difficult and surgical correction is fairly straightforward.

Sometimes after trauma, infection or prior surgical procedure the normally fairly slick membranes (there are several) around the bowels form fibrous connections known as adhesions, which prevent it from doing its normal wiggling as it passes food along its insides. If the bands become tight they too can stop the passage of food forming an obstruction.

Volvulus, is when a segment of bowel does its normal “wiggling” and ends up making a complete twist on itself leaving not only a blockage but a segment full of food which goes nowhere and stagnates.

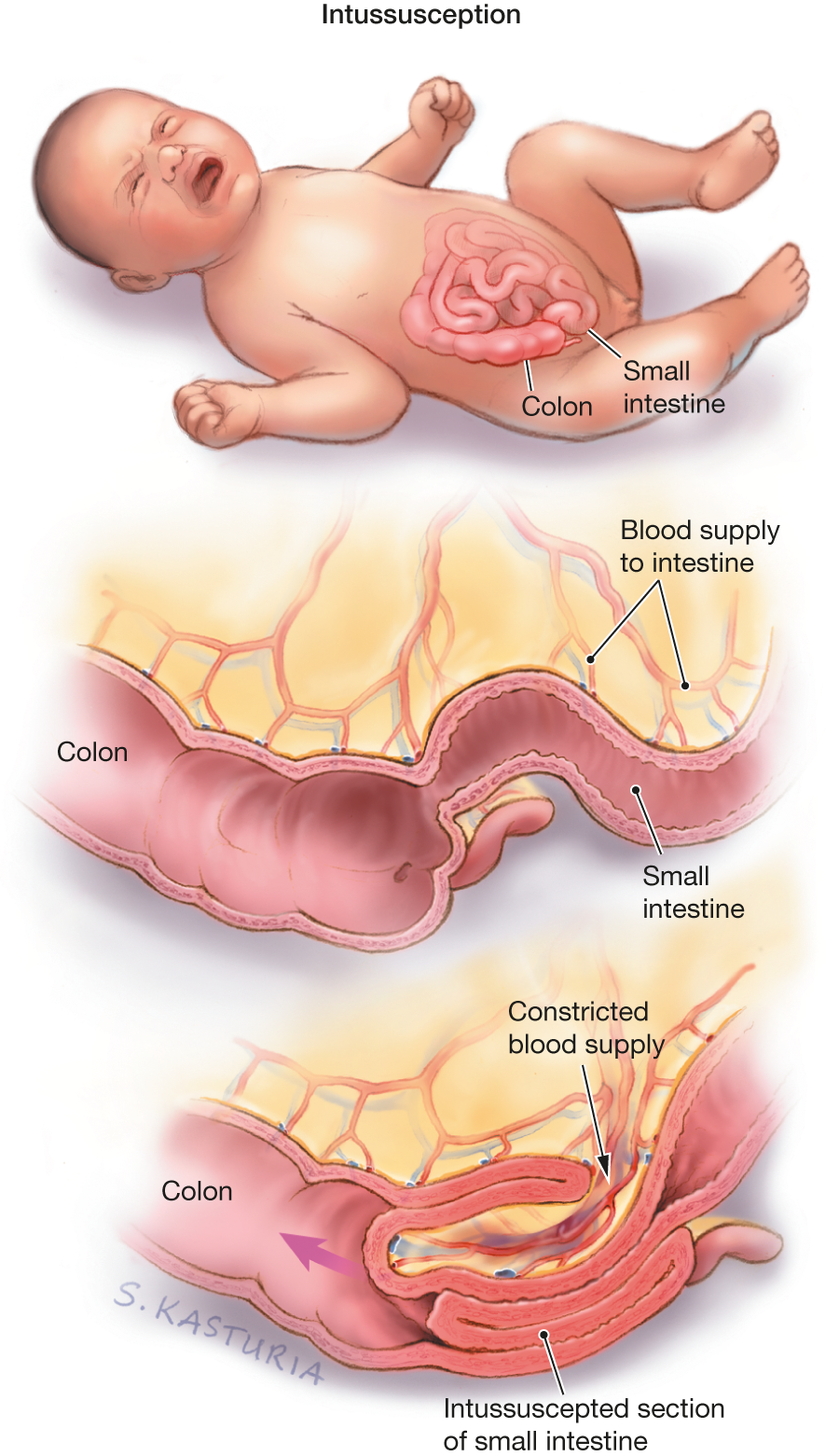

Finally, intussusception is where either a weakened “flabby” area forms or a particularly strong “wiggle” tries to go against firm food and a portion of bowel is pushed inside itself in sort of a telescoping fashion.

The problem with all of these is not merely having to do with preventing food from going through. The dangerous issue is due to the fact that the blood vessels supplying the bowel run along the membrane outside the bowel where they too are easily blocked. In that case the bowel they supply is strangled and dies.

Intussusception in Children

Now you know why bowel obstructions should be taken seriously in children and why there is some urgency in diagnosing and treating them. Sometimes waiting to “see how he/she is in the morning” isn’t the best approach; even if the baby’s belly pain is only diagnosed as “colic” by the ER.

Let’s discuss the last cause on the list, Intussusception, which has recently gotten some “press” and prompted some questions. Knowing how we diagnose and treat this issue will aid in understanding the others as well if they come up.

Types and Incidence

Statistically, the “mode” (most frequent number) for intussusception in children is 5-10 months; but, the “range” actually spreads from birth to adulthood—being weighted toward childhood and adolescence.

We see two “variants” namely: an intussusception between both the small and large bowels (ileocolic junction) known as “idiopathic intussusception“; and, an “enteroenteral intussusception,” one between two sections of just the small bowel.

“Idiopathic” just means that we don’t know (yet) why some kids get it and some don’t and effects mainly infants and toddlers; while the eneroenteral type occurs in older children associated with some other medical situation like cystic fibrosis, rare blood problems, polyps or lymph nodes or prior significant surgery.

Despite being little known by the average parent, intussusception actually is the most common cause of obstruction between 5 months and 3 years; and accounts for about a fourth of all surgical emergencies of the abdomen in children under 5. It even beats out appendicitis!

Very rarely, we can also see it in neonates (first 4 weeks).

Physical Findings

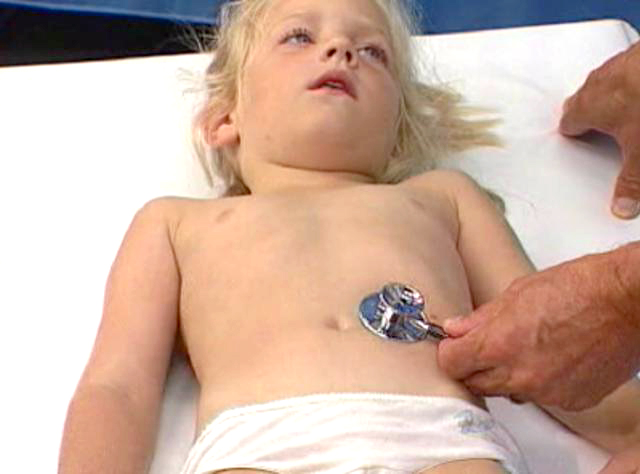

A doctor suspecting intussusception examines for several different things like a distended belly, blood in the stool, tender abdomen; but, there is one finding (if it is seen) which is fairly “classic” and considered a “hallmark” of intussusception—the “Dance sign.”

At least that’s what doctor’s call it (probably after some Dr. Dance but I don’t know) and it’s a bit difficult to detect in a baby who is not happy and most likely crying. If one takes the time and can carefully feel the lower abdomen on the right side with your fingertips you might feel a sausage-shaped mass midst otherwise emptiness.

If the obstruction is total there is distention in the upper belly. If enough time has caused death and some gangrene of the bowel there will probably be rigidity and guarding from peritonitis.

Early in the process there is often a “positive test” for blood in the stool even though you don’t see it visibly (called occult). Later on frank blood (hematochezia) looking like currant jelly is seen for a stool.

A fever and blood signs of an infection are usually late signs indicating breakdown of the bowel and gangrene.

And, to top it off, often patients with intussusception have no classic signs or symptoms; which, unfortunately, delays diagnosis with bad consequences.

Diagnostic Tests

What diagnostic tests a doctor performs depends a bit on where he thinks the obstruction is and how long it’s been there; but, these days it’ll probably begin with an ultrasound of the abdomen which has become the standard of care.

Especially in the ileocolic type, ultrasound is very sensitive and specific for intussusception; however, sometimes abdominal x-rays or other imagings are helpful.

Of course blood work will be done if there is any suspicion of infection, blood loss or damage to the bowel.

Treatments

Of course most of the time, especially in their infant, parents would love to have the problem resolved without surgery—and in some cases, but not all, that may be possible with a “therapeutic enema.”

Just as the diagnosis is helped by considering the patients age, the treatment options can be considered by age too.

The first thing to be said however is that if there is any suggestion that the intussusception is severe enough to have caused bowel compromise or infection, in either of the types, then careful surgery is the only option.

That being said, grouping patients into those under three years and over is quite helpful. Those under three years, i.e. those with idiopathic intussusception who rarely have a “lead point,” may respond to a therapeutic enema and be able to avoid surgery.

Those over three years, i.e. the ileocolic or ileoileo types, usually have a “lead point” weakness or abnormality of the bowel which produces the intussusception so they will easily return. So, children over 3 and those who have failed an attempt at a therapeutic enema are taken to surgery; which, these days, can be done endoscopically so is quite a bit less stressful.

Like I said, any evidence of perforation or peritonitis are absolute contraindications to an attempt at non-operative enema. In addition, there are other things the doctor considers as well such as those which we’ve seen that increase the likelihood of failure.

In addition to what I’ve already described, these things seem to increase the failure rate of non-operative treatment:

- Symptoms over 24 hours

- Increased neutrophils on blood work

- Rectal bleeding

- Small bowel obstruction on x-ray

- More than 5% dehydration

- Younger than 3 months or older than 2 years

- Even, an inexperienced radiologist (doing the therapeutic enema)

All of these are considered before the doctor describes the approach he/she is going to recommend for treatment.

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)