Leg Pain on One Side in Children – Perthes Disease

Leg pain on one side, without known injury, usually means that a child (usually a boy) needs to see his Pediatrician for a thorough exam. Boys, as most parents know (and despite the political attempts at uni-sexing children), are a lot more likely to inflict injury on themselves due to their general activity preferences.

Staying inside on a good day is not a good sign for a boy

If the soreness and tenderness a boy is having is due to the general “rough and tumbleness” of boys, it will nearly always also be general in nature – i.e. both-sided. Leg pain or other musculoskeletal pain which is only one-sided is pretty much expected to be due either to some sort of localized trauma or injury or something internal.

So, lets take the case of a 9-year old boy who complains to his mother of soreness in his left leg on a weekend. [Another aspect which should make a parent suspicious – a complaint which interferes with play rather than school.]

As 9-year-olds often do, his description was vague and he pointed his finger around his leg between the knee and hip when he was asked: “where does it hurt.” [Yet another suspicious action because if it’s an injury, it usually has a very definable location to a child. Although the leg pain in Perthes Disease is often referred to the lower leg somewhere or buttocks.]

Mom’s “come inside for awhile” advice seemed to work and nothing further was made of it for a couple of months until he again complained of pain in the left leg, only this time it was said with quite a bit more intent. Because it was a school-day, Monday, little was thought about it until Saturday when his mother called for an appointment with their families practitioner.

Mom described his left leg pain to the receptionist but when the “sore leg” didn’t seem to energize the office receptionist to anything shorter than a two-week-away appointment, she decided to take him into the Emergency Department at the Pediatric Hospital; who, understandably, were much more solicitous about seeing the problem on a weekend. [Parenthetically, hip pain increasing in severity should NEVER ever be triaged by a receptionist. It also NEVER deserves a two-week-out appointment in anyone, especially in a child – even if that means the doctor and nurse need to stay during lunch or after closing on that day … that’s my feeling about it… The doc does get a point for having at least Sat AM office time though.]

The board certified pediatrician on duty had no difficulty diagnosing the boy’s leg pain with the not-common, but not terribly unheard of disorder: Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease – LCPD or “perthes’ disease” for short.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease

It was first described in the medical literature over 100 years ago by three doctors: an American, Arthur Legg (1874-1939); a Frenchman, Jacques Calvé (1875-1954) and a German, Georg Perthes – hence the name: Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease (LCPD). [Being listed last gave Perthes most of the credit when the inevitable shortening of that too-long-to-pronounce name was given its common nick-name.]

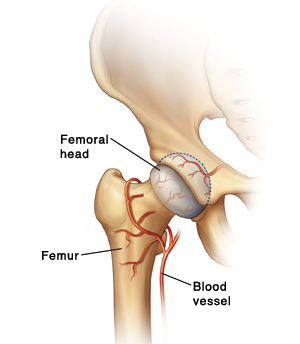

It has now been found to be the result of a vascular inadequacy to the actual head of the longest bone in the body, the Femur. Without adequate blood supply the cartilage and bone of “the ball” which fits into “the socket” of the hip withers away and dies.

Eventually the disintegrated bone does fill in with new bone and scar tissue so I guess one could call it a “self-limiting” disease; but, it’s the actual state of that ‘filling in’ which determines how functional and how life-limiting the condition eventually is to the child.

The new bone replacement may be so complete and perfect that a reasonable facsimile of a normal bone may result. It totally depends on the age of the patient (the younger the better), the presence of associated infection, eventual alignment of the involved joint, and other mechanical and physiologic factors.

Even today we still don’t know exactly what causes this avascular necrosis (disintegration due to lack of vasculature) in about 4 of 100,000 children (one in 1200 children younger than 15 years) mostly between the ages of 4 and 10. A further puzzle is why it afflicts four to five times as many boys as girls and more whites than other races.

A disease which afflicts less than about one in two or three thousand individuals may be considered a “rare” disease but it isn’t so rare that nearly all actual children’s-medicine trained Pediatricians haven’t seen and cared for at least one or two in their practice.

Physical Exam For Leg Pain

Back to our limping boy with leg pain – his mother only adds that he’s been normal except for being on the small side of the growth chart. He eventually confides in you that the pain comes and goes, seems to be getting worse over several weeks, “doesn’t make me cry” because he can “sit down.” And that it “mostly hurts here” pointing to the inside of his left knee but then moves it up a little to his thigh.

While undressing for the exam you notice that he puts little pressure on his left leg and winces just a little. When he walks he has an “antalgic gait” (favors one leg by shortening the time spent bearing weight on it – a limp); and you notice that he is at the eighth percentile for both height and weight.

However, there’s a LOT of things that can cause a limp in a child so you methodically go through them in your mind while you examine his leg. He doesn’t have a fever and his vital signs are normal – less things to think of. There is no warmth, erythema (redness), swelling, bruising or visible deformity in either lower limbs – even less things to think of.

Oops, when you feel firmly in the femoroacetabular (hip) joint on the left he grimaces and groans – not good. You first ask him to move his right leg through range-of-motion (sneakily trying to find out what is normal for him) then note that the same motions are limited and guarded on the left.

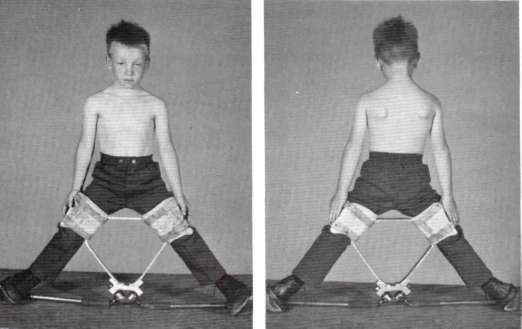

You let him rest on the exam table and ask him to bend his knees. The left knee seems just a tad bit lower than his right indicating possibly some shortening of the femur; and when you let him rest his knees outward – like a frog – his right rotates outward more than the left (see photo).

These findings are repeated when you have him rest his leg in your hands and you passively move his leg around the same motions, so the next step is a bit of lab work and some x-rays.

Diagnosis of Perthes Disease

Because you know you’ve spent the time to obtain a good history and done a good examination you’ve almost narrowed the diagnosis down in your mind. None of them are really good but some better than others. The blood work (CBC, ESR and CRP) were all fine as you thought, hoped, they would be; but, the x-ray did give you the diagnosis: LCPD, Perthes Disease.

You see a smooth, rounded top to his right femoral cap (top of leg bone) but the one on the left is all “ratty looking” and uneven. [Remember the right side of x-ray is his left hip.] Not nearly as degenerated as it could be for a nine-year-old though – that’s a good thing.

Actually, LCPD is the most common cause of a persistent limp in a boy who is between 4 and 10 years old, so your experience has told you all along that it was most likely Perthes; but, still, you owed it to everyone to make sure it wasn’t something like osteomyelitis, pyogenic arthritis, transient synovitis, abscess of the psoas muscle, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, hemophilia, slipped capital femoral epiphysis or cancer – to name a few off the top of your gray, old head.

Treatment of Perthes Disease

Something which sets Pediatricians off from other specialties seeing children in their practice, is probably a greater understanding of, and commitment to, being a child advocate through all aspects of their life. And, that actually doesn’t make your next step any easier.

You realize that the boy’s treatment actually begins with your very first talk with him and his mother, even before you put on a brace or give him a wheelchair or introduce him to his new “friend” the orthopedic surgeon. Eventually this will resolve in some way, but there is a “long row ahead of them left to hoe.”

How he comes out of it in the end depends upon whether or not they can focus on some good goals of eventually getting back to play and not on “pity” or “crisis management” type aspects of life. A huge amount depends on parents getting over the “feeling sorry” for him and into the “let’s see what we can do for now” mode of operation.

[Actually, you are looking forward to seeing them again and helping him and his family work through this. After all that’s why you took the trouble to get board-certified in pediatric and adolescent care, right?]

The first thing mom wants to hear is that: “it’s not cancer or a tumor”; so, that’s the first thing you say and pause to let it sink in.

Perthes disease isn’t common but it’s not so uncommon that we’re flying in the dark over treatment. X-rays might actually have been UNhelpful and we’d still be doing tests on him like a bone scan; but, they were and we don’t have to in this case.

There will probably be years of treatment but the eventual outcome these days is usually, in fact often, quite good and there’s a good chance he’ll eventually be able to participate in sports again. There used to be pretty much only one treatment but now every child gets his own plan depending on severity and age.

The younger the child, the better the outcome. Nine is getting “up there” but at least the x-rays aren’t as bad as you have seen them in other cases. There needs to be complete rest of the leg – NO KIDDIN’ – until you and the pediatric surgeon decide on the course of treatment which could include: casting, bracing, physical therapy or surgery of several possible types.

Immobilization

This is an absolute must to the extent that the progression of the disease dictates and in many ways is the most difficult thing for an active boy to tolerate. There is hope however and these days plenty of alternate activities to weight bearing.

It’s the continued weight bearing which can cause the greatest detriment to the goals of treatment. We need to eliminate hip irritability, restore and maintain good range of motion in the hip, prevent collapse of the bones’ growth centers (epiphysis) and eventually attain a spherical head to the femur when we’re done.

The whole process of disintegrating and re-growing bone, muscle and vasculature is a time consuming process – usually four or five years or more. Protecting the joint so that it can heal in a “rounded” fashion well up inside the “socket” of the hip is the tough part.

It can only be accomplished by keeping the femur abducted (flexed outward at the hip) and internally rotated (toes turned in) for a long time. Braces and casts do that – and once was pretty much how we did them all. Now days surgical techniques have changed a lot and we really shouldn’t manage a child like this without consultation help from a pediatric orthopedic surgeon who has experience in this surgery.

Casts and Braces

Braces and casts are what they are – a royal pain in the tookus. Whether to use a brace or a cast, at what angles and for how long entirely depends upon the bone. And even once that is decided, there are many different types of devices.

Transportation, toilet activities and other hygiene issues, dressing and keeping other joints as mobile as we can are all things taken into consideration, which is why there is so much variety.

But, medical devices don’t do it all. There is always a lot of home-grown innovation and DIY by parents and other care-givers. Moms nearly always develop sewing skills to modify clothing with snaps and Velcro. Dad’s tinker and refine various “contraptions” to solve a multitude of perceived difficulties and make life easier for everyone.

Surgery

This is probably where the greatest amount of change in treatment has occurred. Several different techniques have been developed to solve different kinds of problems.

Surgery does not speed healing of the femoral head, but it does cause the head to re-ossify in a more spherical fashion. And we have found that the new surgical techniques and skills can improve and even shorten how long casting is needed.

Physical Therapy

The advent of computers has given medicine the ability to re-examine, combine and analyze massive amounts of data on nearly everything and Perthes is no exception. Here-to-fore impossibly large studies are revealing surprising implications for treatment.

The disease seems to follow different patterns for children under 6, between 6 and 10 and over 10 years of age. Early surgery is best for some and there’s even a suggestion that bracing can be abandoned in others. It all depends on the stage and extent of the problem.

But uniformly the use of physical therapy procedures has grown not only to strengthen upper body muscles to deal with wheelchairs etc., but to improve flexibility and range of motion in the affected hip and knees.

Outcome of Perthes Disease Treatment

It is common now to see the younger children eventually return to sports activities; and even some children who were older or with more extensive bone compromise as well. The eventual function all depends on the amount of deformity that occurred when the bone was softened and whether or not damage or premature closure of the growth plate occurred.

As we’ve said, nearly all children eventually heal well and can return to activity.

When we say “long term prognosis” it refers to the potential for osteoarthritis of the hip as an adult; which, understandably, occurs more often when the patient was: 10 years or older, had more complex involvement leaving residual deformities and where there was involvement of the growth plates.

If osteoarthritis occurs, total hip replacement can be considered.

Additional information about Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease

If you’d still like to learn a little more about the leg pain the boy had, I’ve included below a couple of web videos: a “report” from the ABC television network and a summary from a doctor at the Mayo Clinic.

Mayo Clinic

ABC Report

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)