Meningitis In Children

We’ve done this before but in this case history I won’t make you guess. It was between me and my “professor” many years ago. Attendings and residents both saw clinic patients but residents also had hospital ward rotations. An attending “summoned” me from the hospital to admit a child sitting quietly on her mothers lap in absolutely no distress.

Petechia on arm of child with meningitisFamiliar with this attending, I knew that this was going to be one of those “guess what I’m thinking,” adversarial teaching-moments he liked to do to impress patients and mark his territory; but, from his face I read “don’t give me any grief over this.”

Meningitis: Cases

Early Diagnosis

The child had an infinitesimal fever and he had found one single, teensy-tiny, sliver of a petechia (pee-tee-kee-uh) on her left forearm; and, he wanted me to admit her for a meningitis workup!

Before my eye contact with him could even register its plea, he said “here’s the doctor who will be taking care of you tonight” and rushed us out of the room. Petechia are merely tiny broken capillaries beneath the skin and can mean anything from NOTHING to merely crying hard, to blood problems – to meningitis. And he had only found ONE!

Just as I was thinking “this kid doesn’t look sick” she quietly laid down on her mothers lap and gave a long protracted sigh. I felt her forehead and she seemed to be burning up. Her fever had come on within the 15 minutes since it had been taken.

Resignedly I picked the child up in my arms and headed, with the mother, to the elevator because NOW she really did look sick. (Yep that’s how we did it back then when we didn’t want to wait for a gurney to be brought from the other side of the hospital.)

In the elevator she seemed to go to sleep and by the time we hit the treatment room on the ward she was so lethargic she made absolutely no fuss as I laid her down and felt her neck. She had a stiff neck and she resisted my flexion with a whimper.

Lumbar puncture, sitting, teenage girlI turned to the mother, who had obviously seen the change in the child too, and said: “We need to do a spinal tap and start an IV; but, I better get started right now if that’s alright.” She nodded her assent and I saw the nurse put her hand on the woman’s shoulder.

Lumbar puncture, sitting, teenage girlI turned to the mother, who had obviously seen the change in the child too, and said: “We need to do a spinal tap and start an IV; but, I better get started right now if that’s alright.” She nodded her assent and I saw the nurse put her hand on the woman’s shoulder.

From that point I sort of lost track of what was going on behind me and had the child prepped, draped and was in the middle of the spinal tap before the rotating nurse even had the IV tray out ready to insert the IV. The girl didn’t raise a whimper during the whole thing. When the spinal fluid began dripping into the tube I could tell immediately it was Meningitis because there was cloudy fluid instead of the clear liquid it normally was.

I said (to the nurse) “If you’ll go get the antibiotics I’ll put in the IV”… and we did.

Until the culture was completed there was no way of telling the exact cause of the infection but we were able to make a pretty good guess and begin treatment – because I had already done blood cultures while starting the IV. A good thing too because I was then paged to the Emergency Room – stat!

When I turned around to leave I finally remembered the mom because she was sitting next to the wall looking pale. She had seen the whole process without making a sound and looked exhausted.

She had heard me tell the nurse the diagnosis and be paged so knew I had to leave; however, I was able to at least say: “that actually went pretty well and perhaps we’ve caught this really, really early” before leaving the nurse in charge of explanations, admission paper-work and putting the girl to bed.

Late Diagnosis

In the ER I was greeted by a very anxious first year surgery resident who was doing his mandatory rotation through the ER and wasn’t at all happy about needing to see patients which weren’t surgical. He told me about a 10-year-old boy he had been seeing for a couple of hours with vomiting and a “possible appendicitis”; but who had been “getting worse even though all his surgical workup, including CAT scan of the belly, had been negative.”

The boy had gone to school well but developed a 103°F fever and threw up so was sent home. He had now spent two hours in the ER getting a “surgical workup.”

I glanced at the surgeon’s history and physical notes while walking to the room – which didn’t lead to any semblance of a diagnosis except that he had vomited a second time. Only an exam of the abdomen was documented. Apparently, to him, vomiting could only mean appendicitis and nothing else.

One quick glance at the boy from across the room however gave me all the adrenaline I needed to ask the nurse to run for a pediatric lumbar puncture set.

He was alert but undressed, hot with fever, and looked like he was afraid I was going to move him; which I did, gently, just enough to see he had an almost board-stiff neck that even hurt when I lifted his legs.

I introduced myself to his parents in the same sentence that I told them I felt things were urgent enough that we needed to talk while I started an IV. They agreed, relieved that someone else had caught the urgency that they had been feeling for hours.

I had blood cultures drawn and IV started when the nurse returned with the LP set only to be sent back for antibiotics. The child didn’t respond at all when I turned him on his side to do the Lumbar Puncture; which, for the second time that evening, was cloudy and obviously infected.

Child in ICU with meningococcal meningitis and purpuraOn the way to the ICU he was still unresponsive and became incontinent of stool. Slipping him into bed I noticed petechiae all over his chest and abdomen. Without even the culture results I knew the diagnosis: Meningococcal Meningitis. It seemed to be “going around.”

Child in ICU with meningococcal meningitis and purpuraOn the way to the ICU he was still unresponsive and became incontinent of stool. Slipping him into bed I noticed petechiae all over his chest and abdomen. Without even the culture results I knew the diagnosis: Meningococcal Meningitis. It seemed to be “going around.”

Meningitis: Diagnosis

The term “meningitis” merely reflects an infection of the meninges (filmy coverings of the brain) and NOT the cause. It can be caused by several different viruses and by several types of bacteria among other things.

These two cases were almost classic of meningitis caused by the bacteria Neisseria Meningitidis commonly referred to as meningococcal meningitis – excruciatingly contagious, highly virulent and amazingly rapid!

Clinical manifestations

Children commonly present first with general symptoms that don’t point to a diagnosis (nonspecific) including: fever, vomiting, myalgia, lethargy, diarrhea and abdominal pain.

Classic signs of meningococcal infection, such as petechial or hemorrhagic rash, mental status changes and signs of meningitis (vomiting, headache, photophobia, stiff neck, positive Kernig’s or Brudzinski’s sign) may not be present initially but often develop abruptly 12 or more hours later. The absence of signs for meningeal irritability does not rule out the diagnosis.

Vascular complications

As I said a lot of things cause meningitis, which is bad enough; but, Meningococcus also attacks the body’s blood vessels as a “kicker.” The inflammation will then either make them “leak” (extravasate) or possibly even “clot off” (thrombose).

Loss of blood into the skin can cause shock and a whole host of secondary problems. Thrombosis of any vessel causes a “stroke” of that body part and can lead to amputation or death.

If vascular permeability increases in the lungs it results in pulmonary edema and respiratory distress. If uncontrolled, it can trigger a whole-body coagulation problem (DIC) and bleeding from nearly everywhere.

Meningitis: Treatment

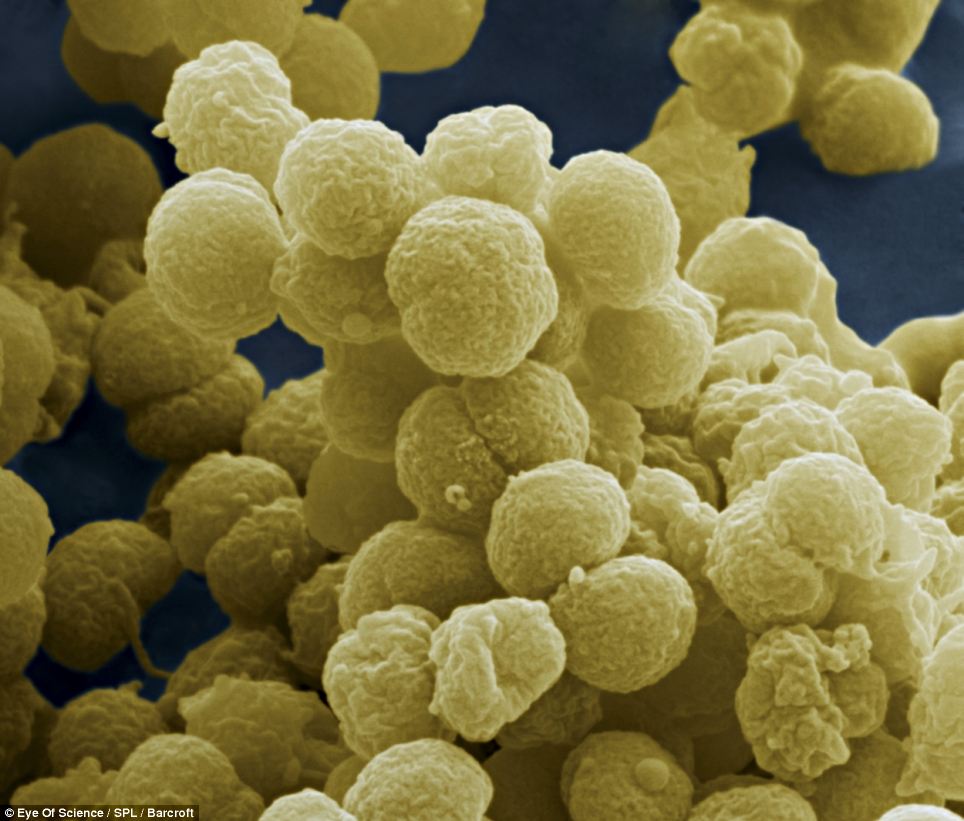

Scanning microscope view of meningococcus bacteriaPurpura fulminans occurs in 15% to 25% of patients with meningococcemia but may be prevented by early diagnosis and intervention with antibiotics and adequate fluids.

Scanning microscope view of meningococcus bacteriaPurpura fulminans occurs in 15% to 25% of patients with meningococcemia but may be prevented by early diagnosis and intervention with antibiotics and adequate fluids.

I guess that would be the whole point of this article and which I learned all at once on the same day — “THE BEST TREATMENT IS EARLY DIAGNOSIS.”

Real pediatricians everywhere know first hand that: “if you aren’t doing several lumbar punctures which come back NORMAL on patients then you aren’t being suspicious enough” and one day you’ll have a patient die or have other bad complications because you missed catching it early.

The first patient was sitting up and fussing the next day and home in four days. The latter was barely on the mend when I rotated off service three weeks later and had suffered side-effects he would need to “live around” for the rest of his life. It’s a BAD disease.

There are antibiotics which can be used to kill the bacteria – the “good news.” BUT, I have to tell you, most of the time with this disease, treating the meningitis is the “easy” part.

Making the diagnosis after an eager doctor has indiscriminately given antibiotics without knowing the diagnosis, chasing blood pressure and fluids, keeping them breathing, stopping the bleeding, preventing amputation and a hundred other issues – now that’s the “real” tap-dance.

In the years since this “lesson” from that attending I’ve learned that his “lesson” was, in fact, what he did often when he saw a patient in the clinic with a petechia as a “teaching opportunity” for the residents and that we had “lucked in” by accident to a real case of meningitis. I know that because he was as surprised as I was when I presented the case in rounds the next morning.

But that was the lesson we all need to learn: accidents can either be of the “unfortunate” or “happy” variety – largely depending upon how prepared you are.

It’s something that I’m seeing all too frequently these days in doctors. You can’t hope to find something unless you’re looking for it – and doing a decent physical examination.

Meningitis: Prevention

Did I mention that the best treatment was: Prevention? Thank heavens we now have an immunization against nearly all the serotypes of meningitis caused by Neisseria Meningitidis. It occurs almost 10 TIMES more frequently in developing countries than in developed thanks to immunization programs.

Transmission occurs with direct human to human contact or respiratory droplet exposure, so attacks children younger than 2 and adolescents between 15 to 18 (those ages with proclivity for bodily contact.) College freshmen living in dormitories and military recruits are at significantly higher risk for invasive meningococcal disease.

Approximately 1,500 to 3,000 cases occur annually in the United States. Mortality (death) rates as high as 20% in some age groups – and sequelae rates equal that beginning 5 or so days later as bleeding and immune complex-mediated symptoms kick in.

Post Exposure

In both of these mentioned patients a whole posse of public health workers contacted family, classmates and other intimate contacts who were examined, warned and preventively treated with antibiotics. Only one classmate contracted the disease.

In school or day care settings, children, caregivers and teachers in the same classroom or childcare room should be treated with prophylaxis. Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended for health care workers providing mouth to mouth resuscitation, endotracheal intubation and suctioning. Approved treatment includes rifampin or ceftriaxone in children and ciprofloxacin in adults.

Pre Exposure

Universal vaccination of all children was advised in 2006 for 11-12 year olds!

In the years since then we’ve also found that the immunization can be safely given as early as 6 weeks of age to certain high-risk children AND that the immunization needs a booster at 16-18 years in order to be effective during the second peak of increased risk.

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)