Common Pediatric Sports and Recreational Injuries – Fractures

We’ve written about common summer problems in previous posts. But we’ve got a new crop of kids going out the front door now this season and a new crop of parents worrying about their bumps, bruises and fractures.

Ankle fracture common summer injury

So, I thought we would take another stroll through the list of common things kids and parents should be vigilant about in hopes of possibly preventing a few – and at least fore-arming you should accidents strike.

This year over 38 Million children and teens will participate in organized sports in the United States alone – and that’s not counting informal recreational activities.

That will mean that over 2.6 million of them will be treated in an emergency department for a sports/recreation injury – and that’s just those under 19!

Sports and Recreational Injuries in Kids

The most common, of course, are sprains, strains and bone injuries but repetitive motion injuries, heat-related illnesses and concussions aren’t far behind in numbers. Of equal concern though are cardiopulmonary problems, infections and exposure to insect species.

Let’s briefly discuss them and talk a little about how we treat them.

Children’s Fractures and Growth Plates

Fractures in children are quite a bit different than those in adults. The risk of a child sustaining a fracture increases with age and with sex – i.e. boys have the greatest “risk” but I don’t suspect girls would be any different if they all acted like boys.

The upper extremities suffer the greatest risk and the statistics are starting to show a relationship with obesity and increased fracture risk. The “top 10” riskiest sports are: football, basketball, soccer, softball, volleyball, wrestling, cheerleading, gymnastics, and track and field.

To begin the discussion, the X-ray shown above has a vertical fracture (red arrow) of the left ankle and reveals one of the greatest areas of concern: it might damage the bone’s “growth plate” (physis) to cause growth deformation. This fracture is in what we call the “epiphysis” and does NOT cross the growth plate (blue arrow).

On the other hand… the X-ray to the left shows a fracture too – only the sneaky little blighter is straight along the growth plate (red arrow) and would be completely missed by any doctor who hadn’t seen a 100 good X-rays and didn’t notice that this physis was ever-so-slightly widened.

Why does that even matter? Well, if the doctor said “it’s normal” and sent the kid home it wouldn’t be with a cast or instructions for follow-up. The fracture is bad enough by itself; but, if the bone continued to be used, even further damage would be done to the growth area and probably wouldn’t be noticed until it was too late to prevent substantial limb shortening.

A child’s increased bone flexibility, decreased density, proportionally stronger ligaments and tendons and developing growth plates all make growth-plate fracture more likely and treatment more complicated. So much so that doctors need to categorize fractures differently in order to predict future problems and direct the varied treatments.

SALTR Classification of Children’s Fractures

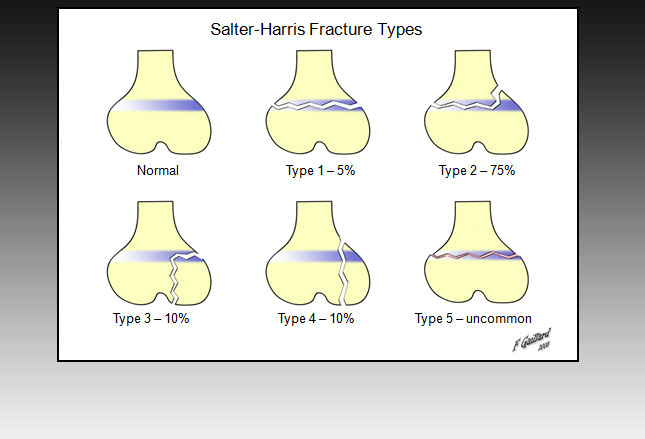

Just so you will have some idea of what the doctor is talking about, I’ll give you a list of the 5 types of children’s fractures, those 5 which involve the growth plate known by the eponym: SALTR

- S – Type I = “Slipped” or “straight across.” Fracture of the cartilage of the physis (growth plate).

- A – Type II = Above. This is the most common type of Salter-Harris fracture. The fracture lies above the physis.

- L – Type III = Lower. The fracture is below the physis in the epiphysis.

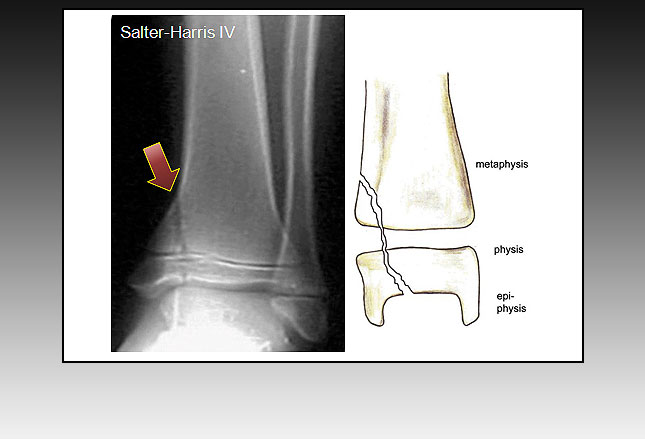

- T – Type IV = “Transverse” or “through” or “together.” The fracture is through the metaphysis, physis and epiphysis.

- R – Type V = “Ruined” or “rammed” (crushed). The physis has been crushed.

Treatment of Children’s Fractures

The whole outcome of a child who sustains a fracture of his growth plate rides on its severity, site, classification, plane of injury, age and current growth potential (i.e. how far along in puberty they are – hence growth plate closure).

Using broad generalizations, SALTR type I and II injuries often can be treated with casting/splinting if you are very careful and re-examine in 7-10 days for signs that healing is progressing without signs of the fracture opening up (i.e. “maintenance of the reduction”).

The more severe types III and IV – the intra-articular (inside the joint) fractures – usually require the doctor to cut open the joint, put it back together and “fix” it place with screws or something, also known as “open reduction with internal fixation.” That way they can carefully avoid crossing the growth plate and making matters worse.

This photo (left) is of a child’s X-ray who has sustained a SALTR IV fracture at the ankle. The red arrow marks the superior end (top) at the Tibia and is clearly visible running downward, across the growth plate and into the joint space (epiphysis, physis and metaphysis respectively).

An additional problem with types III and IV is that they are “intra-articular” fractures (inside the bendy-joint) which can also damage the cartilage – thus causing deformity of the joint or arthritic pain.

Treatment for type V fractures, the crushing kind, often involves cast immobilization with the expectation that surgical intervention will probably be needed to restore bone alignment after the body has done what healing it’s going to do or the child has become an adult with closed growth plates.

Stress Fractures

Repetitive motions and muscle overuse, as commonly seen in children’s sports, can result in tendinopathy (pathological problems of the tendon) and stress fractures (repeated stress which causes structural failure and fracture).

In the photo at the right, the growth plate in this teenagers Tibia has closed and is not really visible; but, the blue arrows show a stress fracture (Disruption and failure of a bone due to repeated stress) whose inflammation “juices” have caused “periosteal elevation” (bulging of the lining on the outside of the bone) at the red arrow.

A number of things cause stress fractures; such as, excessive exercise, increase in exercise, poor mechanics, weak musculature, and hormonal deficits. They are often not visible on X-rays even though they are causing considerable discomfort.

You can treat them with rest, ice and elevation. If you eventually need to see us for the pain we will probably use a splint or cast with crutches.

However, that might still leave the poor muscle mechanics which might have caused it in the first place to go un-addressed. Therefore, we often prescribe physical therapy sessions to correct those as well.

Incomplete Fractures

Fractures in children are often not completely through and through because their bones are less fragile, softer and have a greater ratio of collagen to mineral. These have been given special names depending upon their look, cause and location: greenstick, bowing, buckle and torus to name a few.

If one side buckles upon itself without bothering the other side, it’s called a “buckle.” Greenstick’s splinter along the “grain” and don’t bother the other side either; however, their sharp ends may poke through the skin and cause what it known as a “compound fracture.”

Impact and force along the length of the bone (longitudinal) curves the bone in a bow – hence, “bow fracture” – and Torus or buckling fractures are caused by impaction like in the photo to the left of a child who fell on his wrist and fractured his distal radius.

If they are not particularly severe we can treat them with merely some kind of immobilization like a splint or cast; if not, we might need to finish breaking them in order to get them aligned and back into place. That, of course, is a whole different level of treatment requiring some kind of anesthesia.

Clavicular Fractures

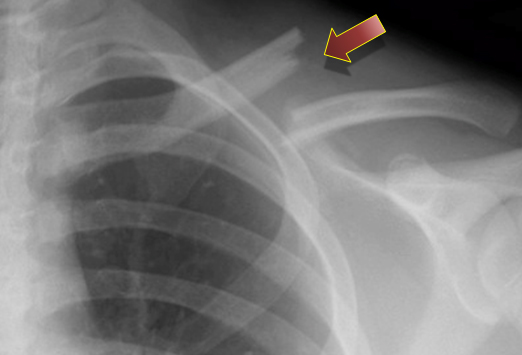

Just as helmets don’t prevent concussions, shoulder-pads don’t prevent fractured clavicles; they may protect against them but not prevent them – especially if they are not expertly and properly fitted (as they most often are NOT).

It’s rare for a physician to miss one of these because they not only hurt (a lot) but are nearly always easy to spot on an X-ray. They’re comparatively easy to treat too (at least for us); but nearly always keep reminding the child that he’s/she’s injured until the bone callous heals to a level of firmness and bridges over the break.

The only “immobilization” technique we’ve got for the shoulder is a figure-eight type of strap – which doesn’t quite prevent movement enough to stop spasms of pain in forgetful moments of jostling.

Other treatments are analgesia, arm support and physical therapy; then, watchful waiting as the large bump remodels itself to look (sort-of) normal over a few years.

The thing is though: your doctor should really examine the child fully afterward because fractured clavicles should ALWAYS prompt consideration of additional injuries (like damage to the brachial plexus, among other things) – which are usually of no small significance.

If a brachial plexus injury is missed there may be loss of sensation or muscle control in the arm, wrist, hand, or fingers and could require surgery.

Dislocations of Joints

Probably more than clavicles, I’ve treated hand and wrist sports injuries the most. And the thing is with injuries in these areas: delayed diagnosis and treatment of hand injuries can lead to significant morbidity, because many long-term complications are dependent on the timeliness of treatment.

By that I mean: waiting to see if it hurts and swells, then going to see the doctor in the morning instead of seeking immediate evaluation at an ER, not infrequently turns an injury that could have been treated with something like a cast into a full surgical intervention by a hand-specialist-surgeon and possibly a permanent disability.

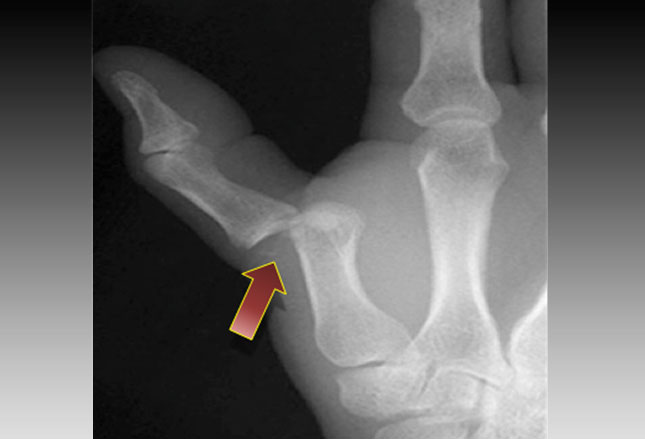

The X-ray image on the left clearly reveals a quite displaced dislocation of a child’s thumb at the metacarpophalangeal joint.

Nail Plate Injuries (open fracture)

Ok, the final thing (but not the least thing) about fractures I want to write about today is this:

Most people wouldn’t call smashing the end of your toe into something hard when you missed kicking the ball “stubbing your toe”; but, that’s what your son will probably tell you when you ask him why he’s limping after a football game.

A smart parent will follow that with “I’m sorry, let me see it” because it wouldn’t be unusual to see a hugely swollen blue thing with a large hematoma under the nail and possibly even a sharp angle where it starts to head “south.”

In children the growth plates of all digits are so close to their nail plates that a subungual hematoma (painful bubble of free blood under the nail) is often caused at the same time as a growth plate fracture. If you see one, then you absolutely must make sure you don’t have the other too.

In the photo to the right the blue arrow is pointing to the nail bed injury, the red one to the completely displaced growth plate fracture.

While common language might not have an adequate term besides “stubbed toe” there is no shortage of medical names for this significant injury; not the least of which is the clever: “the Pediatric Stubbed Great Toe” (with emphasis on “the” and “pediatric”). It’s even used when smaller toes are involved. Another term is a Pinckney fracture.

When the kid “stubs a finger” it’s called a Seymour Fracture.

AND, this combination of injuries is always considered an “open fracture” AND we ALWAYS treat open fractures with antibiotics!

2 Posts in Sports Injuries (common-sports-injuries) Series

- Sprains to Infections – 14 May 2016

- Common Fractures – 10 May 2016

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)