Thanksgiving Dinner: Then vs Now!

It was over TWO HUNDRED years after it was first “eaten” (the dinner) before Thanksgiving (the holiday) became “officialized” in the United States.

Every pre-school child knows about the Pilgrims eating their first harvest meal with the Wampanoag Indians. They might not know the dinner was in 1621 and that Abraham Lincoln made it a national holiday in 1863; but, they do know about gratitude and being grateful—or at least I hope they do.

Thanksgiving Prayer, traditional US holiday of thanks

The gratitude came from surviving in the unknown even if they weren’t yet thriving. And it came from the feeling of abundance the harvest brings after eking a living day to day during lean times.

The pilgrims (and later the pioneers) were used to sharing; so, doing so with their “neighbors,” the Wampanoags, wasn’t even a hard decision—after all, in many instances, the harvest had been entirely due to their instruction and help.

Thanksgiving Dinner

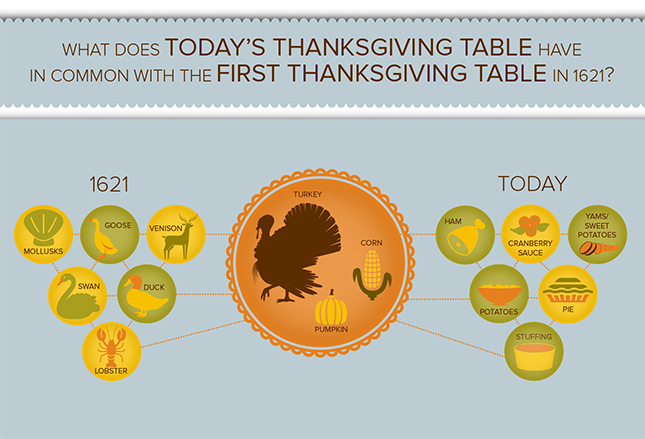

Comparing Colonial vs Contemporary

You know of course that I’m referring to the “Thanksgiving” which is the purely USA tradition memorializing the fortitude, bravery and courage of those persons who had become so disgusted with the oppression and their lives in England they were willing to “step off the edge of the earth.”

Those willing to suffer the consequences of the unknown for the inalienable freedoms taken away from them by kings, queens and other despots.

I know that it’s likely people in other countries may have similar traditions; but I’d like to take a crack at comparing Thanksgiving “dinners” then and now. The food with which the pilgrims celebrated their first harvest bounty compared with what we now choose to use to give thanks. I believe that the difference holds true for other cultures and countries too.

The Godmother of Thanksgiving

Unfortunately (for us), nobody jumped up from that first thanksgiving feast and said “hey, let’s make this a national holiday.” That was left, 206 years later, to Sarah Josepha Hale, a novelist and poet, who got a bee in her bonnet that the date should be honored with a tradition. And, being the woman she was, she just kept nagging and promoting it everywhere she went until somebody had to listen!

She introduced her obsession to America in her first novel, Northwood—a Tale of New England, where she had a “typical farming family” eating a “typical Thanksgiving meal” and described it in excruciating detail:

The table, covered with a damask cloth, vieing in whiteness, and nearly equaling in texture, the finest imported, though spun, woven and bleached by Mrs Romilly’s own hand, was now intended for the whole household, every child having a seat on this occasion; and the more the better, it being considered an honor for a man to sit down to his Thanksgiving dinner surrounded by a large family. The provision is always sufficient for a multitude, every farmer in the country being, at this season of the year, plentifully supplied, and every one proud of displaying his abundance and prosperity.

The roasted turkey took precedence on this occasion, being placed at the head of the table; and well did it become its lordly station, sending forth the rich odor of its savory stuffing, and finely covered with the froth of the basting…. There was a huge plum pudding, custards and pies of every name and description ever known in Yankee land; yet the pumpkin pie occupied the most distinguished niche…

She would have done Cecil B DeMille proud!

It took 20 years of her nagging and wheedling, however, before she became an editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book and was able to publish the news that: “The Governor of New Hampshire has appointed Thursday, November 25th, as the day of annual thanksgiving in that state. We hope every governor in the twenty-nine states will appoint the same day—25th of November—as the day of thanksgiving! Then the whole land would rejoice at once.”

She began publishing numerous recipes for the “Thanksgiving Feast” and as they say… the rest is history. Now let’s get on with the comparison of today’s Thanksgiving dinner with, not the stylized theatrical version, but the “real original” version—as best we can discern it.

Then: Wild Birds, Venison, and Seafood

All we know about the dinners “Then” comes from personal journals of participants and their families which reveal that Governor Bradford dispatched four men to hunt wild birds—which most certainly were: wild turkey, geese, swans and ducks. The Indians brought five deer and seafood was all around them.

Small fowl: Roasted on a spit over open fire. Large fowl: Boiled, to create a broth and make sure it was cooked clear through without burning it. Then it was roasted to crisp the skin.

Deer: Made into a hearty stew. Venison is much lower in fat than most animal meats, 3 grams per serving versus 9 grams per serving. Meat contains high amounts of protein (24 g) but venison is lower in calories (125 vs 240) and higher in iron (3.3 vs 2.1 mg) per serving.

Fish, lobster, mussels, oysters, and clams: Their abundance along the coast made these a staple at every meal. Lobster, of course, is high in cholesterol; but, ocean going fish are high in Omega 3 fatty acids.

Mussels have the most nutrition containing high levels of long-chain EPA and DHA fatty acids, which improve brain function and reduce inflammatory conditions, such as arthritis. And they are an excellent source of zinc and iron, as well as folic acid and vitamin B12.

Now: The Broad-Breasted White Bird

Farmed Turkey: Today, the wild turkey is eking back from the brink of extinction and is protected. What we buy in the store is commercially bred, reaches up to 50 pounds, incapable of flying and must be artificially inseminated so is raised in single sex flocks!

While almost all meat (even breast) from a wild turkey is dark meat with more intense flavor, commercial birds of today are brined and injected to “enhance” their flavor which is predominantly white meat.

Dark meats: Contain higher levels of zinc, B vitamins, and amino acids. Commercial turkey has less protein than wild turkey (24 g versus 26 per 3.5-ounce serving), 20 less calories and a similar amount of fat (1 g). Because it is nearly always brined or injected (either in packing or in recipes) it can contain up to 800 mg of sodium per serving—versus virtually no sodium in wild birds.

Then: Stuffing With Herbs and Onions

Herbs and onions made up most of the flavorings for wild game back then and did so without any calories, fat, cholesterol or sodium. Add some Chestnuts, which were natural flora back then, and wild rice and you’ve got a full “dressing” for any type of wild foul.

Chestnuts: Lower in calories and fat (213 calories, 2 grams of fat per 100 grams of nuts) than other nuts and contain a rich 43mg of vitamin C. As do other nuts they are rich in monounsaturated fatty acids (Oleic and palmitoleic) which help lower total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and increase high-density lipoprotein (HDL) to prevent coronary artery disease and strokes.

Now: Bread-Based Stuffing or Dressing

Now-a-days “stuffing” or “dressing” or whatever-you-call-it is heavily based on bread, fat, meat and salt—although it is probably the most “regionalized” portion of the Thanksgiving meal across the nation.

Commonly it contains: croutons or breadcrumbs, sausage meat or turkey giblets, onions, celery, carrots, sage, and poultry seasoning. A half-cup of this mix contains 105 calories, 4 g of fat, and 336 mg of sodium.

Regional additions, the south substitutes cornbread or biscuits and includes bacon or salt pork; the north uses white, wheat or rye bread. New England adds oysters (high in omega-3 fatty acids but also in cholesterol).

Oysters, apples, chestnuts or other tree nuts, cranberries and raisins may be added based on regional availability and preference; which, obviously, also changes the nutritional profile given above—and not toward the healthy side.

Instant stuffing: This “convenience food” became an “instant success” after it was invented by Ruth Siems in 1971; by 2005 over 60 million boxes were sold for thanksgiving alone. One cup, the traditional Thanksgiving-sized serving, has: 2.2 grams fat, 858 mg sodium, 150 mg potassium, 2 mg cholesterol (if not embellished), and 40 grams of carbohydrates for a total of 214 calories.

Then: Potatoes Were a No-Show

Potatoes came from South America, sweet potatoes from the Caribbean and neither had been imported at the time of the Pilgrim’s! Potatoes were a “no-show” at the dinner table. The Spaniards brought potatoes north around 1570.

Instead other plant roots abounded in the woods and fields, like:

Turnips: These may have been brought by the native American’s who used them all the time. These amazingly tasteful vegetables are very low in calories (28 kcal per 100 grams), high in antioxidants, minerals, vitamins and dietary fiber.

Perhaps the most under-appreciated vegetable on the store shelf, they are hugely rich in vitamin C (21 mg), a potent antioxidant required by the human body for synthesis of collagen. And it aids the body in removing harmful free radicals to prevent cancer and inflammation and boost immunity.

Now: Mashed and Sweet Potatoes Are a Holiday Staple

The south imported sweet potatoes from the Caribbean earlier than the white potato appeared. White potatoes became readily available in the US around the 1700’s and by the mid-70s had become a North American staple.

Sweet potatoes: Slightly higher in calories than white potatoes (90 vs 70 calories per 100 g) but are a rich source of flavonoid antioxidants, vitamins, minerals, and dietary fiber.

Sweet potatoes have a higher amylose/amylopectin ratio which increases blood sugar levels rather slowly compared with simple fruit sugars (fructose, glucose) and is a healthier for people with diabetes. They also contain many essential B vitamins along with vital minerals, such as iron, calcium, magnesium, manganese, and potassium.

Candied: Casseroles topping sweet potatoes with a marshmallow topping are very popular Thanksgiving dishes in America. Marshmallows became commercially available in the early 1900s. A serving of marshmallow sweet potato contains 256 calories and a whopping 31 g of sugar!

Then: Stewed Pumpkin

The Pilgrims and the Wampanoags ate pumpkin at their harvest feast; BUT… not as a pie! Native Americans either roasted or boiled pumpkins for centuries before the Pilgrims arrived. (There was no butter or wheat flour with which to make a pie crust, nor an oven.)

A Pumpkin Custard was made, according to historians, from roasting a hollowed out pumpkin shell—filled with its meat (pumpkin flesh), milk, honey and spices—in the hot ashes of the fire.

Pumpkin: One of the highest sources of vitamin A (7384 mg per 100 g) with an abundance of flavonoid polyphenolic antioxidants (lutein, xanthin, and carotenes). Vitamin A maintains the integrity of the skin and mucosa, and is also essential for good vision.

Pumpkin also has zeaxanthin, which may offer protection from age-related macular disease in elderly persons. Studies also suggest that foods rich in vitamin A may help protect against lung and oral cavity cancers.

Now: Pumpkin Pie

Leave it to the French to have invented pumpkin pie, back in 1653, by boiling it in milk and straining it before placing it in a crust.

In America it was published as a recipe by Amelia Simmons in 1796 using American ingredients. She also included recipes for all the pies that made it into the Thanksgiving “lexicon”: Apple, pumpkin, mincemeat and cranberry tart.

The pie still has the healthy antioxidants and vitamins of pumpkin, but the average recipe contains 323 calories per slice, 13 g of fat, and 25 g of sugar—compared with stewed at 26 calories per 100 grams.

Then: Side Dishes of Vegetables and Fruits

Native “Indian” corn: was not eaten on the cob dripping with butter as the hybrid corn is today. It was dried and pounded into cornmeal then cooked into a thick porridge.

Fruits: Those indigenous to the Pilgrim’s region included the: blueberries, gooseberries, raspberries, plums, Concord grapes, and, of course, cranberries. Cranberries were used by the Wampanoag for natural dye, a medicine, and as a preservative (it contains benzoic acid).

A big problem at the FIRST Thanksgiving was that the Pilgrim’s supply of sugar they brought with them was way too scarce to use bringing such a tart fruit as cranberries up to palatable levels. So, they wouldn’t have made cranberries into a sauce or relish. Fruits abundant, sugar scarce.

Fresh Cranberries: Have health benefits from their phenolic flavonoid phytochemicals (polyphenols) which protect against tooth cavities, inflammatory diseases, cancer, aging, neurologic diseases, diabetes, and bacterial infections.

We also think their antioxidants may benefit the heart by counteracting formation of cholesterol plaques in the blood vessels, lowering LDL and increasing HDL cholesterol levels.

Now: Cranberry Sauce and Green Bean Casserole

I’m going to get green beans, casserole or otherwise, out of the way first thing. I do acknowledge, and am sorry to say, that green bean casserole is just as firmly entrenched into the Thanksgiving tradition in my neck of the woods as turkey.

BUT, as far as I’m concerned, those suckers have absolutely no socially redeeming value—which, according to the supreme court, makes them equivalent to pornography and should be banned in public, private and anywhere populated by humans.

Whew! That out of the way, making a casserole out of the distasteful things was invented as a marketing gimmick in 1955 by the Campbell Soup Company to promote sales of their creamed soups and canned fried onions—and it doesn’t take much brain power to work out that the Campbell company single-handedly turned something with basically zero nutritional value into a puddle of high-calorie, high-fat, high-sodium glop…

I think it best to move on to cranberries—probably the best source of nutrition in the whole Thanksgiving dinner of today!

Cranberries: Everything that green beans are not, cranberries are. Since the early 1800s they have been used in the US for sauces and an accompaniment to meat. As an extremely high source of vitamin C, General Ulysses S. Grant ordered cranberry sauce served to his troops in 1864 (perhaps to prevent scurvy).

In the early ’30s, cranberry farming switched from the very labor-intensive dry harvesting to wet harvesting using mechanical techniques which exploded their availability to the public—albeit in canned form due to the machinery damaging their skins. The even more convenient cranberry jelly took off as a Thanksgiving condiment.

These days, with improvement in machinery, even fresh, whole cranberries are universally available and are preferred nutritionally over the canned form.

So, there you are. If you want to “go back to your roots,” and eat more healthy at the same time, make the main course of your Thanksgiving dinner lean wild venison, goose, duck, mussels and seafood whose “stuffing” is onions and herbs.

Turn to sides of roasted vegetables available natively like turnips and carrots with nuts and fresh fruit. Make “the lack of sugar” one of the ingredients of the menu; and, if you must pay homage to today’s fare, make it sweet potatoes and cranberries. Oooh, pumpkin custard for dessert.