When Doctors Don’t Do A Good Physical Exam – Patients Loose

Not so long ago, in collaboration with the Washington Post, a clinical news source for physicians called “Medscape” [which I read frequently] ran an article entitled “When Doctors Don’t Do A Good Physical Exam Patients Loose.”

Siblings ready for a good physical exam

Unfortunately, they put it in a format that only can be read by people who are “logged in” and you have to give them your state license number and a bunch of other things in order to “register” to log in; so, the average patient has no hope of finding out “when doctors don’t do a good physical exam.”

That’s why I decided to paraphrase the article for you – so you’re not left out. There is really no ‘secret’ to what makes a good physical exam. I’m sure that if you ever get the chance to be on the “receiving end” of a poor one and a good one you’d be able to tell the difference without even the need to scratch your chin!

I’ve spent much of my career doing quality assurance activities in the hopes of preventing patients from “loosing”. So, why is it that even I (who absolutely knows what a good exam consists of) haven’t been able to locate a personal physician since I’ve moved a few years ago who will bother to do more than impatiently listen to a cursory history, type in his computer to make Obama happy and only half-heartedly listen to my heart?

They might look right at me as a new patient , talk medicine and order tests with only a cursory listen to two areas of my heart. Do they think I don’t realize they’re skipping and short-changing me? Or, perhaps they think I just won’t care.

I guess I’m supposed to think they’ve done a good job when I receive the bill with a code signifying: “complete physical, new patient!” and a price to match.

The question is: “Do you?”

Sloppy Doctoring and The Physical Exam

Can any of you (who are old enough to actually remember “service” stations) ever remember being asked by an attendant “is it running smooth” before he decides whether or not he will even bother to check the oil level? Of course not – that’s absurd! You want to catch low oil levels BEFORE they have a chance to RUIN YOUR CAR! And, you cannot tell anything about the oil level through questions – you’ve got to LOOK.

Anyone who thinks a doctor can diagnose an enlarged spleen by simply asking “do you feel anything in your belly”; or, testicular cancer by asking “anything else wrong, you know, ‘down there'” just simply doesn’t understand how medicine works. You’ve got to LOOK… or feel… or listen.

The “History Of Present Illness” (HPI) and “Past Medical History” (PMH) are two of the major portions of the complete physical exam record that every physician is taught meticulously in medical school. You tell him/her what’s going on now and other problems you’ve had in the past.

Then he’s supposed to go through the “Review of Systems” (ROS) which is a long list of symptoms that was originally and specifically designed as a “cheat sheet” for him to use as a method to be compulsive and trick himself into not to missing anything. Of course the tedious ROS was the first thing to go out the window with the invention of the computer – most doc’s decided to make YOU fill out your own ROS long ago – crossing fingers that YOU knew enough medicine to “guess what they’re thinking” with all the questions.

These three portions of the standard physical exam documentation are often critical in making some diagnoses; BUT, only as an adjunct to the fourth major part: the actual “Physical Exam” (PE). You know, that portion where you actually get undressed and he/she pokes, prods, listens and feels from the top down.

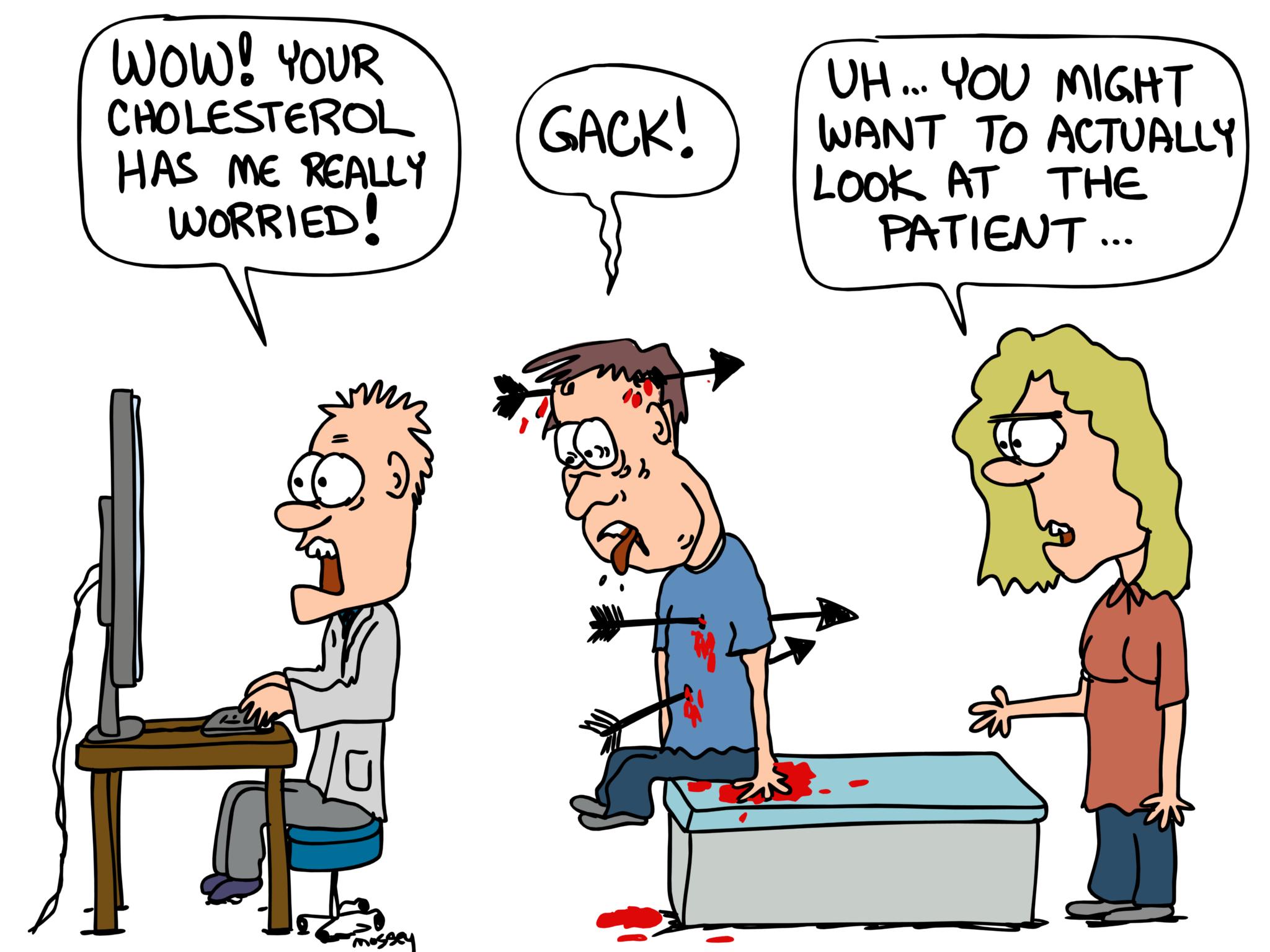

If doctors aren’t doing physical exams any more then upon what are they relying to make a diagnosis? Lab, X-rays and other imaging studies.

In medical school I had a classmate who right from the beginning stood at the head of the dissecting table and took notes while the rest of us followed the designated procedures. We called him ‘The Anesthesiologist’ of the group.

Thing was, he didn’t change much as we progressed into the clinical years. On the hospital wards, if a nurse told him that a patient had a fever, he would first run to the chart and hope that someone had already given him the answer in an X-ray or blood work or nurses note.

Finding anything, he would frequently begin treatment on what truly was an assumption without even walking into the patients room to possibly see that their IV was inflamed and needed to be removed.

He worried us, but back then we didn’t have a cute name to call him; “anesthesiologist” didn’t fit any more. These days we might have called him ‘tech support’ or the ‘IT’ department.

He seemed to have great difficulty in relating with patients; and, fortunately for all of us, realized it himself and had the integrity to pursue a career path in research where others would provide the patient interface.

Other examples elucidating the problem from the article:

Missed Breast Cancer

A 40-year-old California woman had been to doctors over the past two years and even hospitalized several times. Admitted yet again, her physicians were worried about “her sky-high blood pressure and mental confusion” and after their workup ordered a CT of her lungs because they had “diagnosed” that she might have a blood clot.

It was a complete and total surprise to them that the scan did not reveal a clot but several large cancers in both breasts which now had spread throughout her body.

The sad thing was that had they, or any of the many physicians she had seen for her increasing troubles over two years, done even the simplest of exams they would have easily been able to feel the tumors – back when the cancer might have been more easily treated or even cured.

Wrong Diagnosis and Organ

In Seattle Washington a middle-aged man came to the emergency room for the third time in six weeks. The chart was full of references to “liver cirrhosis” for which he was treated and which, apparently, informed subsequent physicians down the line. They noted his swollen legs and distended abdomen.

Fortunately for him a “veteran” doctor actually did a complete physical exam careful enough to notice a tiny inward pulsation just beneath the man’s right ear which kept time with his heartbeat. Easily seen by everyone who took the time to look for it: the classic sign of constrictive pericarditis – an inflammation and swelling of the sack which contains the heart and was now preventing blood flow.

It is a serious condition requiring rapid life-saving surgery. Thank heavens for a doctor who knew how to perform a good physical exam and did his duty to perform it.

Loosing Ability To Perform A Physical

Most all of us who have spent years in medicine recognize a trend becoming more commonplace as medicine becomes more technology driven (either naturally or politically forced); namely, the waning ability of doctors to use a physical exam to make an accurate diagnosis.

Information gleaned from inspecting blood vessels at the back of the eye, observing a patient’s walk, feeling the liver, checking fingernails and those “embarrassing” areas of breasts and genitals provide valuable clues to underlying diseases or incipient problems.

The physical diagnosis skills that were once the cornerstone of doctoring have withered over the past couple of decades, supplanted by a dizzying array of sophisticated, expensive tests.

Salvatore Mangione, associate director of the internal medicine residency at Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College was quoted in the article as writing: “many cases in which technology, unguided by bedside skills, took physicians down a path where tests begot tests and where, at the end, there was usually a surgeon, and often a lawyer. Sometimes even an undertaker.”

What’s Next?

Mangione is one of several physician educators who are trying to bring back the physical diagnosis skills critical to being the physician that patients need and most expect, whether they realize it or not.

Jefferson is not the only medical school recognizing and trying to implement solutions. In part two of this series I’ll describe the changes in curriculum being made at Stanford, John Hopkins and elsewhere in answer to this definite down-turn in the quality of medicine which patients are only now gradually coming to recognize.

However, lest you think this problem is specific to only doctors we’ll also discuss the political, legal and even public expectation variables which are making medicine an increasingly difficult and much less enjoyable field with the highest “physician burn-out” rate we’ve seen… well, for as long as there has been such a thing.

5 Posts in Physical Exam (physicalExam) Series

- Link to article: Physical Exam, Fading Art – 21 Feb 2016

- Poor Physical Exam - Patients Loose – 17 Feb 2016

- Five serious symptoms never to ignore – 21 Dec 2013

- Diagnosing Heart Murmurs in Children – 12 Dec 2013

- Pediatric Physical Exam – 4 Jan 2012

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)